October 18, 2020 marks the one-year anniversary of the revolt in Chile. In Chile, the US, and beyond, we stand at the intersection of a pandemic, an economic crisis, and growing uprisings against the police. In this tangled situation, demands for police abolition erupt in a context in which many people imagine that only increased police intervention can manage this moment of crisis.

In the US, at least at the level of street mobilizations, the growing desire to abolish the police has overshadowed concerns over a new stimulus package or a moratorium on evictions. It appears that the George Floyd uprising has produced a political crisis that eclipses any potential crisis that a nascent rent strike movement could have produced. Every time it seems the uprising dies down, another video of police murder goes viral and it erupts again with a new ground zero—Minneapolis, Louisville, Atlanta, Kenosha, Rochester. Large numbers of people are now concerned about community self-defense after suffering white supremacist violence and federal special forces’ brutality. Yet amid these new concerns, the ongoing economic crisis presents another unstable terrain for state surveillance, control, and repression. We offer the following reflections from the past year in Chile in an attempt to answer the question central to the global uprisings of 2019: “How can we contest territory in ways that render it ungovernable?”

“It’s urgent to disobey.”

If anything, this past year of revolt in Chile has shown us the power of movements that are not channeled into the social protest paradigm the way that so many past movements were.1 In 2011 and 2012, the plaza occupation movements in Spain and Greece, Occupy Wall Street, and the Chilean and Montreal student movements aimed to resolve the tension between the “peaceful protestor” and the “outside agitator” by seeking to justify direct action to a neutral, liberal audience. Vandalism and rioting were framed as the “voice of the unheard,” conflicts with the police as the defense of a zone for free expression. NGOs and government-ordained “community leaders” were often successful in their counter-insurgency efforts, convincing the broader public that militancy in the streets are criminal or radical elements taking advantage of peaceful, social protests.

By contrast, the movements of 2019 in Hong Kong, Chile, and elsewhere embraced the mantra “be water,” precipitating spontaneous clashes with the police as crews merged into crowds only to disperse and reform again elsewhere. Rather than staging symbolic protests outside the perceived institutions of power, street mobilizations attacked precincts, offices, highways, and the material infrastructure of power. A new generation of front-liners (the primera línea) emerged, learning how to block streets and fight police in order to fundamentally reshape what is possible in street demonstrations.

The past year of revolt in Chile indicates an approach to struggle that does not seek to resolve the tension between “peaceful” and “militant” protestor or “good” versus “bad” rioter. Rather, it seeks to resolve the tension between the movements in the streets and the diverse struggles outside the realm of street mobilizations. Like the other uprisings of 2019-2020, the Chilean revolt did not begin with a social protest making demands, but with the blocking of infrastructure. Evasion masiva (mass evasion), a movement against a metro fare hike in Santiago, rapidly escalated into a nationwide uprising. On the night of October 18, 2019, coordinated metro fare evasion around the city erupted into rioting after police shut down the metro and rumors spread that they had killed a high school student. To quell the riots, the government sent the military into the streets and declared military curfews. This created the conditions for rampant police violence and torture, which only fanned the flames. The uprising spread nationwide.

As the protests continued around the country, people spontaneously gathered for the largest protests in Santiago’s transit hub, Plaza de la Dignidad (formerly Plaza Italia). As in Hong Kong, the front line of protestors—la primera línea—fought the police with shields, slingshots, and protective gear. However, the street battles between the primera línea and the police in Plaza Dignidad were only part of the broader revolt in Chile.

Parque Bustamante to the south of Plaza de la Dignidad.

The destruction of Santiago’s public transportation system over the weekend of October 18 left the city’s economy in shambles. Many businesses that weren’t looted were shuttered and the businesses that remained open had extremely long lines. Many basic services and goods were inaccessible for weeks. However, at Plaza de la Dignidad, a gift economy opened up. Barbers went to the plaza to give free haircuts to people who hadn’t been able to get one since the revolt began, tapping into a century-long tradition of revolutionary hairdressers practicing mutual aid and affording dignity through fashion.

Chilean rebels refused to operate within the social protest paradigm, expanding the struggle beyond street mobilization and transforming the various terrains they inhabit. Indigenous peoples reclaimed land and blockaded rural highways; unlicensed street venders established new unauthorized street markets; poor families squatted land and built illegal urban communities; unpermitted relief initiatives fought government surveillance and control. The power and intensity of the October 2019 uprising lay in the heterogeneity of the struggles throughout Chile, under the slogan “until dignity becomes a habit” (hasta la dignidad sea un costumbre). The diversity of ways people contested how their lives are governed showed that people were in the streets because everyday life had become miserable, alienating, and denigrating. The forces seeking to stabilize the situation had to contend with the possibility that millions of people now believe that only way to begin a life of dignity is to never return to the normal state of affairs. Even when the movement couldn’t hold territory and render it fundamentally ungovernable, the participants gained a new sense of dignity in the incessant struggles in the streets.

A garden in the frame of a smashed advertisement display. “We destroy this world to create a better one.”

The Rhythm of the Revolt

“Supermarkets and stores looted, more metro stations and buses burned. Barricades throughout the center of Santiago and in some of its peripheral, impoverished areas…

Scene One: Near Cerro Santa Lucía around a burned bus. Since the morning, people have gathered there and danced around it to the rhythms they banged on its metal frame… They climb onto the burned structure, jump, hit it, and pretend drive it without destination because it does not move: it is a revolt against the movement of goods that we have become. An old busker sits inside and plays his harp.

Scene Two: The military arrive in Plaza Italia, a vital node in Santiago’s nervous system since the end of the dictatorship. They are guarded by the carabinieros (national police). People scold them, shame them, and tell them to go away. It is not their place to be here. The riots spread throughout the Alameda. Heading south from Plaza Italia there are six burned buses. People spread rumors that the police or government set them on fire. Does that matter right now? It doesn’t matter who did it, all that’s relevant is that they’re burnt.

Scene Three: A looted supermarket in Cerrillos. Basic necessities are taken. The crowd carry out televisions and consumer goods between the blankets, diapers, and various household appliance. Many of the goods are thrown into the barricades. Few people jump in to save the items. Alcohol is brought out, some to drink now and some to save for later. The commotion is contagious, there are songs and dances.”

-From Mejores Tiempos by Circulo de Comunistas Esotericas, translated by the author

A burnt-out bus in Santiago: “An old busker sits inside and plays his harp.”

“People met while dancing on top of burnt city buses to the rhythms they banged on its charred metal frame.”

The Chilean revolt was characterized by a new community born out of the experience in the streets that broke the longstanding discursive categories of criminal delinquent and peaceful protestor, of outside agitator and local citizen. Starting during the nightly curfews, people would meet each other in the streets. Elderly neighbors would bang pots and pans beside the burning barricades that youth erected. Groups of teenagers gathered in the darkened aisles of a looted grocery store. This new community communicated to the rhythm of the revolt: People met while dancing on top of burnt city buses to the rhythms they banged on its charred metal frame. They communicated through smiles, gestures, and laughter. The only ones who perceived the division between militants and pacifists were the audiences external to this emerging community of revolt, who could not speak these new languages of rhythms and bodies.

“If you don’t jump, you’re a cop!”

According to the Circle of Esoteric Communists (el Circulo de Comunistas Esotericos), the real uprising was marked for death on the day it was channeled into protests for a constitutional assembly. While everyone was in the streets celebrating the suspension of normalcy, the self-proclaimed leaders of the left and the government’s opposition desired nothing more than to return quickly to a normal state of affairs. Leftists, academics, journalists, and public officials claimed that the necessary outcome of the revolt was a constitutional referendum. Former leaders of the 2011 Chilean student movement, now politicians, were quick to interpret the revolt as a statement about Chile’s rampant inequality, its privatized healthcare system, or its inadequate pension system. They spread fear that the military could stage a new coup if the protests escalated. They pretended that the new community in the street would prefer to narrow its participation to merely checking a box in a referendum. On November 15, the government and opposition leaders signed an agreement for a constitutional referendum to be held in 2020, and many leftist politicians voted for the government’s “anti-mask, anti-looting, and anti-barricade law.” Despite all evidence to the contrary, they believed that the participants in the movement simply desired for a privileged few to obtain new political positions.

A saxophonist playing “El derecho vivir en paz” with la primera línea.

New Year’s Eve and Other Party Riots in Plaza Dignidad

Yet these attempts to separate the crowd into peaceful protestors and criminal delinquents failed. One leftist politician from the 2011 student movement that negotiated the constitutional referendum was even chased out of a protest. The new community of the revolt continued every Friday in Plaza de la Dignidad, with every element coming together en masse for the 2019 New Year’s Eve celebration.

Ringing in the New Year in Plaza Dignidad.

“Leading up to New Year’s, there was a struggle for control between the city, the police, and the people. The city wanted to depoliticize the celebrations, while the police simply wanted to repress them—both strategies for preventing the New Year from being rung in with the tone of courage, combat, and care that has defined gatherings in Plaza de la Dignidad for the last three months. Christmas and summertime had interrupted the rhythm of the daily protests, and New Year’s wasn’t a Friday, so it was hard to predict whether the action that night would push the envelope, or simply feel routine. We showed up early, while there still weren’t that many people, because there was a huge, open dinner in the plaza that we wanted to partake in.”

“I’ve gotten compliments before for going out with my gas mask and water bottle, I’ve even had cans of beer offered to me after quickly extinguishing tear gas, but on New Year’s, the enthusiasm was at another level. Next to the dinner area there was a little stage, and before long a live cumbia band lit up the crowd. When we got to one of the combative intersections, the front line had gained a full block further than where it was normally kept, and the police were backed far down a side street behind a fence. The water cannon sporadically shot out bursts of spray, but no one was fazed. It was just after sunset and the golden sky reflected off of the ground covered in crowd control water, while encapuchados launched rocks, fireworks, and Molotovs at the police across the fence. We walked around some more and in Parque Forestal we stumble upon an enormous spread of hors d’oeuvres, tended by a totally normal large extended family. They’re bouncing toddlers on their laps and the grandfather, a handsome older man dressed in an elegant polo with a sweater wrapped around his shoulders, offers us wine and snacks. “Please,” he insists. There’s even little kebabs of vegetables for the vegans. A rumor reaches us—there’s another concert happening on top of a theater’s nearby marquee. It’s Ana Tijoux! We cross the plaza through crowds of families and people drinking beer and wearing blinking crowns and bracelets, everything is beautiful and glistening. Even the statue in the middle of the plaza is lit up by neighbors from a nearby apartment building. She finished with an encore of “Cacerolazo,” the first anthem of the revolt, that came out just three days after the first night of riots. Fireworks and flares filled the night sky. A huge banner stretched across the plaza reading, “Only through struggle can we move forward.” Everyone seemed to hold onto this moment, not wanting to let it end.”

-excerpt from an anonymous New Year’s Eve report on Radio Evasion

La primera línea on New Year’s Eve in Plaza Dignidad.

Government officials and the institutional left continued to interpret the plaza’s festivities as protests for a new constitution. However, everyone came to the plaza to participate in the communal events to suspend the alienation of everyday life. Those who came to chant and dance in the street continued to celebrate the militancy of la primera línea. Rather than a political ideology, la primera línea was defined as an experience of the protest that anyone could join. There are no polls to show the legitimacy of the primera línea in the eyes of the people, but polls themselves are only needed by those who need to convince the people of their popularity. Everyone in Chile knows that they were the heroes of October—Piñera’s likeness isn’t mass-produced on t-shirts and stickers, after all. Street vendors sold gas masks, lasers, and slingshots throughout the protests so those who wanted to could participate in the front line. In the neighborhoods surrounding Plaza de la Dignidad, residents formed assemblies, organized meals for the protestors, and worked with Brigadas de Salud (health brigades) to establish field clinics on their street. Rescatistas (rescuers) comprised of paramedics, nurses, and doctors carried injured protestors from the front lines back to field clinics. Support for the movement was shown in the material assistance and resources people provided in the streets rather than a professed endorsement of any of the demands attributed to the movement.

The entrance to the Baquedano Metro station in Plaza de la Dignidad. Entrances to the station were closed when revolt broke out in Santiago, but police continued to use the station as a base of operations. Beyond the pile of rubble, you can see the gate from behind which police would shoot rubber bullets and teargas at demonstrators. It was a daily war of attrition to prevent the police from having even an inch of a window through which to stick their rifles. When demonstrators left, the police would clear away what they could of the rubble pile. This station was also infamous because on October 22, a young demonstrator was taken into the Baquedano Metro station and tortured by police. His testimony about the torture became a media scandal, catalyzing further outrage at the security forces. The “Joker” graffiti references the movie, which came out just before the revolt—depicting scenes of revolt that many demonstrators identified with—and was quickly removed from corporate cinemas.

Contesting Public Space

In the course of months of unstructured protests in every Chilean city, we witnessed a transformation of public space that no social movement could ever win as a demand from public institutions. The revolt had an impact beyond the space and time of street protests, as state officials were afraid to crack down on unregulated use of public space for fear of provoking further response. Despite a new nationwide law increasing the penalty for graffiti, the downtowns of every major city were awash with street art. When officials painted over a city’s walls in the middle of the night, it merely provided an invitation for people to return the next day and cover the city with new art.

Chilean cities belonged to the to the people of the sidewalk in those months of suspended police intervention. In the Southern Chilean city of Temuco, Indigenous farmers (hortalizeras) sold their produce on the downtown’s sidewalks. Visiting the hortalizeras in early 2020, we sat next to our friend, Carlota, and her fold-out table displaying lentils, celery, chard, and other vegetables from her farm. Our conversations were constantly interrupted by passersby who greeted her and asked how her farm and family was doing before buying her produce. “I’ve known many of my customers for years,” she said, “I set up on the same sidewalk each day, and most of my customers come to my table daily to buy what they need.” At the end of the day, the women traded their leftover produce to get the fruits and vegetables they don’t grow on their farms. As they break down their tables, there is a second rush of street traffic as the hortalizeras hand out their unsold produce to Temuco residents.

https://twitter.com/joorge_p/status/1300127162197049344

The mayor has repeatedly tried to evict the hortalizeras. In September 2019, riot police with guanacos (water cannon tanks) and dumpsters arrived to shut down the street market. Police attempted to fine and arrest the hortalizeras after destroying their vegetables and fold-out tables. The women fought back, de-arresting many of their fellow vendors. In the end, only the percussive spray of the guanaco enabled the police to evict the market and arrest eleven women and children.

The hortalizeras have organized a union to co-manage their food market on the sidewalks, to raise funds for the eleven women arrested in September, and to file a claim through UNESCO for protection against the city on the grounds of Indigenous rights—an arduous legal process that will take years to result in protection. And yet, because of the nationwide uprising a month after that raid, the hortalizeras were able to resume selling in the streets without fear of police intervention. The widespread anti-police sentiment, raucous protests, and public visibility prevented the city from evicted the hortalizeras for fear of triggering even greater clashes in the streets.

Tomaterrenos in Chile’s Urban Peripheries

Vacant land belonged to the neighborhoods rather than the city government or large-scale landholders. Amid an ongoing housing crisis, poblaciones2 have reclaimed their local environments for their own use against the interests of city officials and land speculators. By February 2020, 48 land occupations (tomaterrenos)3 sprang up around Temuco, where 1500 people had begun to squat land, build houses, and negotiate with the national government for new public housing. The tomaterrenos counted on the support of nearby neighbors who brought water and food to the occupiers, let them use their bathrooms, and helped build communal kitchens and bathrooms at the toma. In response to an attempted eviction targeting one toma, protests erupted throughout Temuco near the other tomas, in which neighbors erected barricades and shut down highways.

A tomaterreno.

The revolt created the conditions for communities to solve their immediate shared problems rather than waiting for government officials to meet their needs. What city officials interpret as a crisis in housing has been reframed by residents as a crisis over their power to decide where they can live and their ability to shape their lived environments. In February 2020, we visited several tomas, including the toma that the police had tried to evict. It was a Saturday construction day. We spoke with Javi and her partner Carlo, who had moved to the toma with their three children from their family home nearby. Carlo explained that

“When the protests started in October, we realized that we had the opportunity to expand our neighborhood by taking control of this long-abandoned space of land, cleaning it up, and building the housing we desperately needed. We don’t want the government to build us houses in some other, far away neighborhood.”

Carlo said, “We want the power to decide what happens to the land in the neighborhood we grew up in and we want to live near our families.” According to Javi, the mayor’s only concern with “public sanitation” is whether or not the city looks modern. As a result, the government doesn’t care about the actual sanitation crisis in the poblaciónes, but only ensuring that it continues to be invisible. Anticipating future evictions, the residents of the toma trusted that front-liners and student groups would help them block and resist the repressive actions of the police.

The primera línea standing in front of the burning “institutional church of the carabineros.”

Indigenous Resistance

New solidarities emerged or were solidified across the divide between rural Mapuche and Urban Santiaguionos, and new urban revolts broke out in response to police brutality against Indigenous communities. The anniversaries of police murders of Mapuche youth have seen some of the most militant protests in the plaza. January 3, 2020 marked the 12-year anniversary of Matias Catrileo’s death; police killed him during a land reclamation action in rural Mapuche territory. On that day, after a Mapuche procession to plaza dignidad, protestors chased away the police who were defending the adjacent carabinero monument and church. Hundreds looted the church and set fire to it. Meanwhile, portable speakers blasted punk music and a crowded circle pit engulfed the vandalized monument.

A Mapuche woman standing in front of a Domomamüll (a Mapuche wooden statue) erected in Plaza Dignidad on December 3, 2020.

For perhaps the first time in Chilean history, Indigenous symbols dominated the imagery of protests in downtown Santiago. Since the 1990’s, Mapuche communities began direct actions against the large-scale landowners and extractive industries targeting their community’s land. Over the past 30 years, the Chilean government has increased the militarization of policing in Mapuche territories, fortifying the logging plantations on stolen Indigenous land. Throughout the Chilean revolt, Indigenous protesters continued to barricade rural highways and sabotage forestry equipment. The visual impact of Mapuche flags outnumbering Chilean flags challenged the claim that the protests were about the protesters’ individual economic precarity or the Chilean constitution.

A Mapuche flag.

The Social Protest Paradigm and the Pandemic

Within the social protest paradigm, it always appears that the tension between “peaceful” and “militant” protestor must be resolved. However, this tension did not materialize in the experiences people shared in the streets of Chile in 2019 and 2020. Rather, outside spectators projected this tension onto the streets as a strategy to channel the revolt into a normative, legible “social movement” for structural reforms. Failing to bifurcate the street mobilizations, they promoted the narrative that the Chilean revolt could be reduced to the ongoing street mobilization, rather than acknowledging the heterogeneous elements of the new community of revolt contesting territory.

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile created a terrain in which it was possible to construct the narrative that the street mobilizations were aimed at presenting demands regarding how public institutions should address the pandemic and the resulting economic crisis. At first, the government applied the quarantine measures gradually. These measures did not themselves dismantle the movements. Rather, the institutional left, social organizations, and trade unions attempted to carry out actions to demand the government implement “a full quarantine with dignity” similar to the “5 demands” in the US. Mall employees staged walk-outs and went on strike until the city closed the shopping malls. When the COVID outbreak began to spread outside Santiago, residents in rural towns and islands blocked logging trucks and ferries transporting salmon industry workers to pressure the government to implement quarantine zones. On March 15, 2020, the government declared a state of emergency, announcing quarantine measures and a nationwide military curfew. As people could no longer go to work, protesters demanded government economic relief. Responding to the COVID pandemic via the paradigm of social protest, making demands rather than directly meeting needs, made public institutions and city officials the protagonists of urban governance once more.

Whether out of fear of COVID-19 or the new policing of public gatherings to enforce quarantine, a critical mass had left the new community of revolt, instead demanding new policies from public institutions and leaders that would do no more than continue existing forms of structural violence. Without the threat of the revolt, public institutions tightened their grip on the areas that had been rebelling.

In Temuco, the hortalizeras were unable to get permits to sell in the street; they were not even able to enter the city, due to military-enforced quarantine checkpoints. When the lockdown ended, they returned to empty streets to sell their produce—but without the commotion of the revolt, the police resumed their eviction attempts. The tomaterrenos suffered a similar fate: while court injunctions blocked further eviction attempts, the city prevented the tomas from connecting to city utilities. While lawyers and NGOs lobbied the city government for resources, the police enforced a quarantine that prevented the neighbors of the tomas from bringing supplies and supporting the occupations. Despite their successes in maintaining the occupations, people began to leave the tomas during the pandemic because they did not have the resources and support to continue them. By August, those involved in the tomas had resumed either staying with family in cramped housing or sleeping on Temuco’s streets.

Despite the restrictions on assembly, the autonomously and informally organized primera línea remained the most legitimate political actor throughout the country. Primera línea demonstrators transitioned from weekly riots in the streets to autonomous public health efforts to support those who had to risk contagion to go to work. The state has had a difficult time reintegrating the autonomous force of the primera línea into the logic and mechanics of political power.

Once the lockdowns made it impossible for the movement to transform the living environment, the state sought to challenge the autonomous, rebellious force within the primera línea. On the one side, statist logic has attempted to co-opt the primera línea into the Apruebo electoral campaign, the side in favor of a new constitution. Gustavo Gatica—whom police blinded with anti-riot projectiles, an exceptional and widely known case in Chile—was recently featured in a campaign ad that looks an awful lot like the propaganda made to fan the flames during the revolt. Now, the dramatic, intimate videos—featuring fare evasion (a crime), graffiti from the streets, and Matapacos (whose name translates to “cop killer”)—are intended to drive you to the ballot box. Before COVID-19, few had faith that their lives could change as the result of the stroke of a pen on a ballot. Yet the power to challenge the forces that seek to channel the revolt towards demanding a constitutional assembly disappeared when the crowds vacated the streets. Only after this could the primera línea to become a symbol rather than an experience.

“Kids of the Plaza”—before such videos were made to support political parties.

The other prong of the state’s approach to dealing with the primera línea is, of course, repression. Yet even in this, they must recognize the power and popularity of the primera línea. In July, at what was perhaps the lowest point of mobilization since the onset of COVID-19, two longtime anarchists—Monica Caballero and Francisco Solar—were arrested on charges related to bombs placed at a police station, an investment company’s posh building, and the offices of a former government minister. While in the formal proceedings, the prosecutor emphasized the apolitical nature of the case, suggesting that the two were arrested for criminal behavior rather than political ideas, the media filled in the rest of the narrative that the prosecutors couldn’t say in court. An August 1 article in La Tercera—known throughout Santiago as the newspaper closest to the prosecutors’ office and police—reads:

“For the detectives, Francisco Solar is the more active of the two. He is constantly invited to anarchist events and participates in the Coordinadora 18 de Octubre (the coordinating body for the freedom of the prisoners from the October 18 revolt), although they categorize his political affinity far from that of the ‘primera línea.’ Although he was one of the people in charge of putting together boxes of food for those in jail for attacks on police during the demonstrations, the term ‘primera línea’ doesn’t fit him. ‘Such a term is also related with discourses and behavior based in the delegation of tasks within the demonstrations, which we see as a threat to the horizontality that has characterized the revolt in Chile,’ says one of the latest editions of an anarchist magazine that Solar is alleged to participate in.”

In short—to divide the revolt, the mouthpiece of the police is willing to grant the primera línea a provisional legitimacy, for the purpose of arguing that participants in the primera línea should not consider Francisco a legitimate comrade because he is alleged to be involved in a magazine that wants to keep the revolt horizontal. The cynicism of this maneuver is staggering.

It’s true, not every primera línea rioter was an anarchist. Many identified as Mapuche, roto (slang for lumpenproletariat), kids from the state-run orphanage system, criminals, feminists, immigrants, otakus, even social democrats. But anarchists participated meaningfully alongside them in all of the greatest battles at the Plaza de la Dignidad: the October 18 weekend of looting and burning, the clashes downtown during the week of martial law, the November 12 general strike, the torching of the police officers’ church, the anniversary of Matías Catrileo’s death by police, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve, not to mention the riots outside the prestigious Viña Del Mar music festival on the coast.

It is absurd to discuss the primera línea and anarchists as separate subjects. Again, there is no independent poll or government census that can scientifically confirm the presence and popularity of anarchist ideas among those who fought police from October to March. But the attempt to divide two well-known anarchist former political prisoners from the primera línea is proof enough of how much the prosecutors and media fear the autonomy, direct action, and informal cooperation—that is to say, the anarchy—of the primera línea.

“Thank you, primera línea!”

Hunger Riots and Community Kitchens (Ollas Comunes)

The state does indeed have reason to fear the primera línea. The cross-pollination between the new militancy in the streets and disparate struggles addressing life and livelihood shows that there are multiple avenues to seize control of urban territory outside of protests. In the months of lockdown, those dismayed at the empty streets and uninterested in Zoom meetings about the constitutional assembly focused on autonomous relief efforts. After months without substantial protests or public activity, spontaneous hunger protests and ollas communes (community kitchens) emerged throughout Santiago in response to food shortages and the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Police deployed the same dispersal tactics they used during the uprising against both the hunger protests and the community kitchens. Police violence against community relief efforts sparked public outrage, especially one video showing a guanaco (armored water cannon truck) running over an olla comun table set with food. In response, the carabineros implemented a permit system for ollas comunes. Regardless, most ollas comunes refused to obtain permits and continued to distribute food without government authorization.

https://twitter.com/rvfradiopopular/status/1197589526190985217

By evading surveillance and social control, autonomous relief initiatives can contest the boundaries of abandoned territories and populations, bringing together disparate, seemingly incongruous social blocs. In so doing, they can subvert longstanding divisions between privileged and marginalized, between formal and informal, between citizen and criminal, between front-liner and homebound, and between network and organization.

https://twitter.com/ComunOlla/status/1312754344689913856

In May, the asamblea libertaria (a libertarian anarchist neighborhood assembly) in Penalolen was invited to help with an olla comun held at an elementary school in a nearby neighborhood. Three people from the assembly showed up to the school with supplies to make 300 sopaipillas. They were greeted by three different groups preparing food: people from Coordinadora Violeta Parra (the Violeta Parra coordinating committee), a neighborhood group formed to rename their street after the folk singer who also distribute milk on a daily basis to children; another Catholic group that makes 300 sandwiches weekly; and a group of moms from the school with to-go boxes and keys to the building. While frying sopaipillas and packing lunches, participants gossiped and explained different projects in the neighborhood. While each olla comun focuses on its immediate neighborhood, they have created the conditions to coordinate across neighborhoods. People from the asamblea libertaria explained that they meet weekly at the Liceo, an anarchist social center with a print shop, popular library, and industrial-sized bakery. At the end of the olla comun, a member from the coordinadora asked if they could use the bakery to make bread for more ollas comunes. Over the following months, comrades used the Liceo to make bread for five different ollas comunes in nearby neighborhoods. In the process of coordinating, they met street vendors who would donate their unsold produce to ollas comunes and neighbors with trucks who would transport supplies.

The conflict between the ollas comunes and state institutions suggests that it is better for the governing institutions if people respond to crisis by demanding structural changes and denouncing government inefficiency than by taking matters into their own hands. These institutions may even encourage autonomous relief efforts, since they increasingly rely on community initiatives to support the abandoned zones produced by the unequal distribution of resources. Yet they are intimidated by autonomous relief initiatives that normalize evasion and provide space for conspiracy. To ensure that autonomous initiatives do not produce a crisis of governance, state institutions enforce exceptional forms of surveillance and social control in order to demarcate the scope, potential, and function of autonomous relief and community action.

Police attacking an olla comune.

The Movement for Dignity versus the Movement for a New Constitution

Although the one-year anniversary of the Chilean revolt is quickly approaching, we are unsure of what the future holds in Santiago. We have seen the discourse surrounding this movement shift from a movement for Dignidad (dignity) to a movement against the constitution inherited from Pinochet’s dictatorship. On October 25, a week after the anniversary of the Chilean revolt, Chileans will vote in a nationwide referendum to decide whether to hold a convention to rewrite the constitution inherited from Pinochet. The institutional left is quick to blame society’s ills on the current constitution—it is a way to divert attention from how the institutional arrangements between the dictatorship and its opposition created this situation.

The last plebiscite took place 30 years ago, when Chileans decided to oust Pinochet. Although the left hails that referendum as the means by which Pinochet was forced out of power, in reality, the negotiations leading up to the referendum were only possible because widespread anti-dictatorship riots throughout the 1980s destabilized the Pinochet regime. The emerging democratic elite created the contradictions we face today when they supplanted the thousands who fought bravely against the military and police in the streets to become the designated leaders of Pinochet’s opposition.

Consequently, our present conflict pits the new community of revolt against both the state and its institutional opposition. This struggle will determine whether the Chilean revolt will be about living life with dignity or perpetuating the institutional arrangements that alienate us from our experiences, our histories, and each other. Despite the ways that the suspension of protests has rendered the community of revolt invisible, we see its presence everywhere. We have seen the fiercest unrest during the quarantine on the days that commemorate the victims of the military dictatorship: the March 29th Day of combative youth and the September 11th anniversary of the coup de’tat. On these days, being in the streets is not about making demands, but being present with neighbors to honor the dead and confront the institutions responsible for their deaths. The movements in the streets have a greater role than just “protecting street marches” or applying pressure to whatever public official walks through the revolving doors of state governance. They serve to create the conditions for other ideas to take hold, for other possibilities to take root.

Since Santiago’s quarantine ended in August, we have seen life returning to the city’s streets and front-liners returning to Plaza Dignidad. No marches were planned, no demonstrations announced. Instead, people began to congregate in the plaza each Friday, as before. At first, increased police presence and brand new anti-riot equipment prevented these crowds of a hundred or so from taking the plaza. Rather, the Friday protests have been cat and mouse games between protestors and police that circulate through the plaza and its adjacent neighborhoods and parks. Yet on Friday, October 2, a police officer was captured on video pushing a 16-year-old child off the Pionono Bridge into the notoriously polluted Rio Mapocho. Tear gas and water cannons delayed the street medic team from reaching the injured child lying face down in the river. The next day, the plaza swelled with outraged crowds and people waved flags atop the iconic statue in the middle of Plaza Dignidad.

https://twitter.com/VitalistInt/status/1314695341443289090

“In the months of quarantine, the city had cleaned the graffiti off the monuments, repaired the sidewalks, and installed new traffic lights and cameras. In the end, this made a fresh canvas for tags, cement to hurl at the police, and material for the barricades. I’ve never seen so many people in Plaza Dignidad since before the pandemic. Street vendors were back, selling flags, masks, beer, and sopiapillas. I don’t think the police were ready for the large crowd. The primera línea was able to tear down parts of the barricades around the monument to the carabineros and throw rocks at the police line nearby. Several marching bands led processions that zig-zagged through the crowds and falling streetlights. But probably the most special part of that day was running into all the friends and neighbors I haven’t seen since the pandemic started. Eventually, a wall of police guanacos [water cannon trucks] and zorrillos [tear gas trucks] dispersed the crowds.”

“I wound up running into some neighbors on the walk back to our neighborhood and we hung out by the rescatista [street medic team] rendezvous point while the rescatistas were coming back from the protest. They had coordinated a full street rescue system like they did prior to the pandemic, going out as crews into the front lines with body armor, shields, and radios to coordinate with the dispatcher, nurses, and doctors at the rendezvous point. When we found out that a rescatista was celebrating their birthday, we wound up drinking in the street with them until some snitching neighbor called a noise complaint.”

-Cristian, eyewitness

While people were reclaiming the plaza, neighbors held small outdoor events to take advantage of the first Saturday after quarantine. A group of neighbors in Chuchunco hosted an outdoor party to celebrate a new mural they painted on their apartment building. Local punk bands, folk singers, and rappers performed on a stage in front of the mural, illuminated by a projector playing a highlight reel of riot footage from the past year. While families were listening to the music, we noticed a small barricade catch fire on the main road up the block. Thirty minutes later, encapuchados (masked demonstrators) began rolling old tires out into the road and ignited barricades on every side of the intersection. Families began to come out of their homes to stand beside the barricades. As the night wore on, no police arrived to disperse the crowd; children continued playing tag in the barricaded intersection.

As movements explode worldwide, government have claimed that shadowy, international networks are behind them. In response to protests in Colombia, the government has already claimed that an “international anarchist nexus” has caused the uprisings in both Colombia and Chile to fuel their anti-police ideology (allegedly, something the effect that “all cops are bastards”). As the ex-worker collective noted, the “outside agitator” trope is an age-old discourse used to delegitimize movements. In view of massive global discontent, it seems that critics will soon be running short on outsiders to blame for the agitation. Yet the institutional left and reformist social organizations have been at least as successful as the authorities at using the “outside agitator” narrative to delegitimize the unrest they seek to gain from.

The “outside agitator” narrative has failed to gain hold here in Chile because the front-liners are part of a broad new community of revolt. It can only appeal to those who have been far away from the revolts and those who seek to spread myths about how movements work. They allege that we owe the victories of the past to social protests—when we know from our own experience that the social protests always come after the nights of looting and fires.

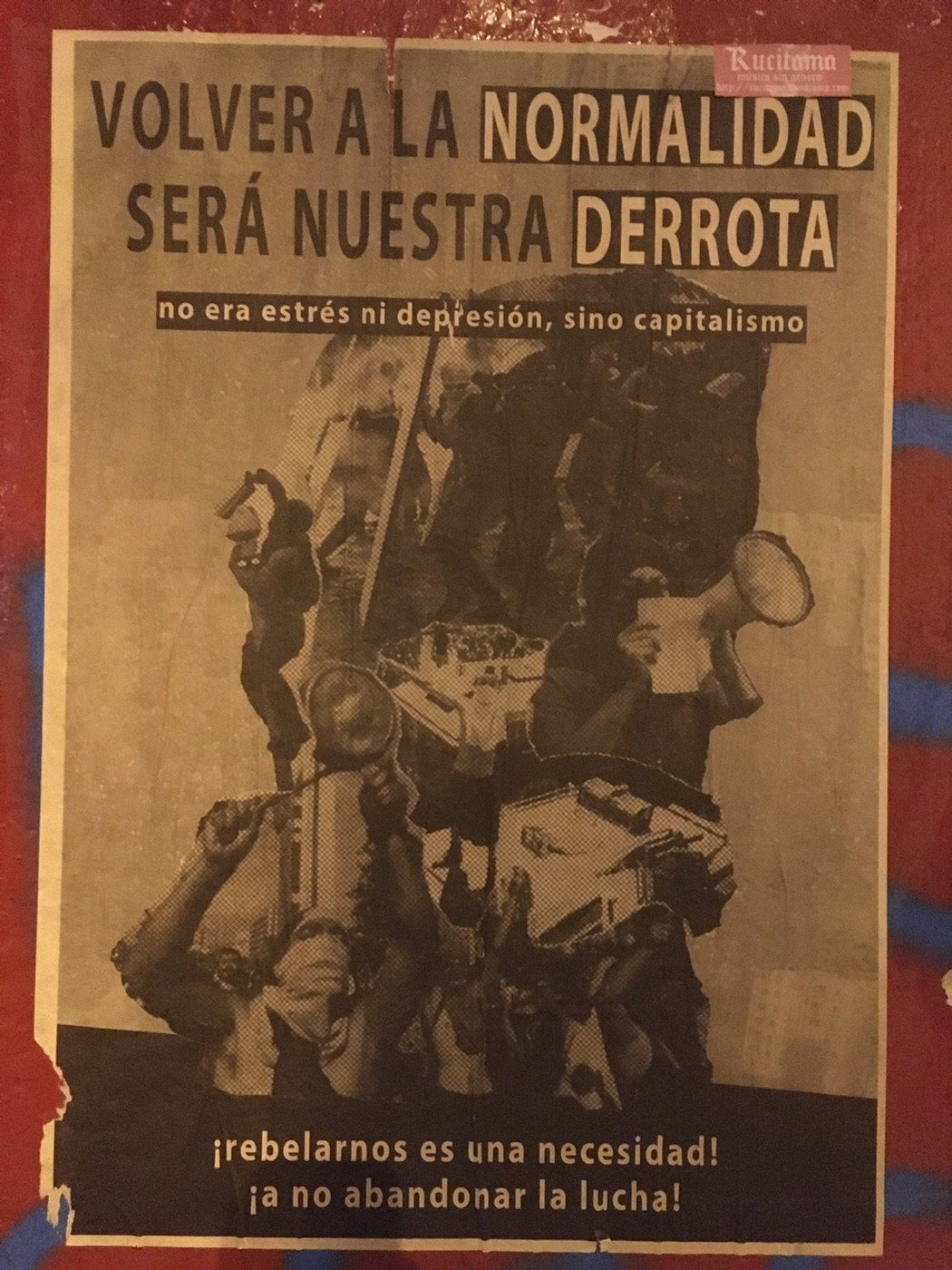

“A return to normality will be our demise. It wasn’t stress or depression, it was capitalism. Rebellion is a basic need. Don’t give up the fight.”

Conclusion

The global surge of rebellions from 2019 to 2020 has revealed a shared community of practice. This bricolage of revolts constitutes a global uprising that breaks out of existing political models. The situation in Santiago differs from other contexts in some ways—for example, the racialization of resource distribution and state violence that prevails in the US has no immediate analog in Chile. Nonetheless, the state violence and intergenerational cycles of poverty endemic to Santiago’s periphery are familiar enough.

The past year in Chile has confirmed that a struggle to contest territory becomes ungovernable when the participants cease to assume that liberal democracy can solve the crisis. No constitutional assembly or milquetoast reform could save us from the ecological collapse that is unfolding, nor could any government official grant us a dignified life. Participation in this wave of revolt is producing the understanding that there is no model of governance in practice anywhere in the world that could offer a solution to the structural violence and alienation we face. At first, many people took to the streets out of rage against police violence or out of feelings of powerlessness and desperation. But we choose to return because we discover that living a dignified life and creating a dignified future necessitate working together to suspend the normal state of affairs. In these moments together, we experiment with new ways to relate to ourselves and the territories we inhabit.

Some names and locations have been altered to protect the identities of participants.

“Inequality is the worst cancer.”

“The democracy of the rich—dictatorship for the poor.” “A patriot—an idiot.”

“No one is forgotten.”

-

By social protest paradigm, we refer to the organizing of street demonstrations that are interpreted as the representation of “the people,” with the understanding that they are building demands to present to the institutions of power, up to and including the dissolution of these institutions themselves. When militant actions occur, they are justified as escalating the pressure on government officials and public institutions to meet the articulated social demands. ↩

-

Las Poblaciones are the neighborhoods that ring the periphery of most cities in Chile. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, urban migrants squatted land and worked together to build neighborhoods and defend their homes from eviction. Residents draw on a long history of revolutionary organizing and subsequent repression during the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990) in their current neighborhood assemblies, neighborhood social projects, and political protests. While these neighborhoods are no longer repressed as the red zone of political dissidents, they are currently policed as the red zone of criminal activity. ↩

-

Tomaterrenos are direct actions in which families without stable housing, either homeless or living with relatives, collectively occupy vacant land to organize a neighborhood and build their own housing. We use the term “tomaterreno” because the closest words in English—squatting, shantytown, and land occupation—all have slightly different implications. Unlike Chilean squats, tomaterrenos are not tied to any particular subculture or political tendency. The participants come from diverse political tendencies; they may even include right-wing participants who engage in direct action alongside communists! We don’t use the term shantytown, because this term simply denotes the ad hoc housing of the urban poor. People don’t participate in tomaterrenos solely out of poverty or lack of housing. Rather, they choose to engage in a collective direct action to seize vacant land together: they plan the action, they map out the land, and they help each other build houses. We use tomaterreno instead of “land occupation” because, for Anglophone readers, the term “occupation” evokes the 2011 Occupy movement and related movements that occupy public space with the vision of building a microcosm of an alternative to the existing social world. The coordination and execution of tomaterrenos are not based on political ideals so much as on material and social needs. The motivating force is the way people desire to live in their environments despite the interference of government agencies and public institutions. ↩