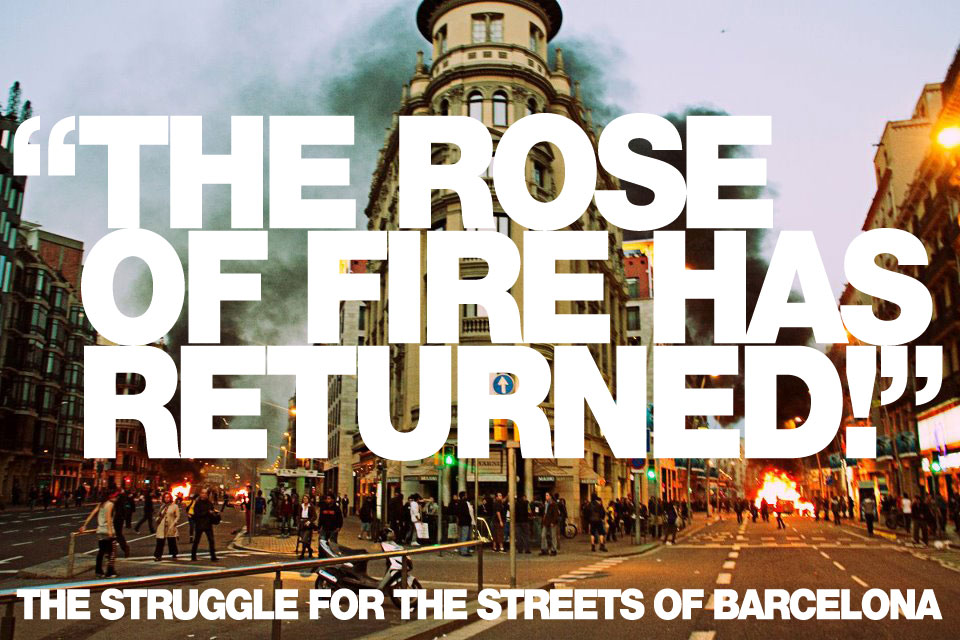

“The Rose of Fire Has Returned!”, The Struggle for the Streets of Barcelona.

In May 2011, tens of thousands occupied plazas throughout Spain in a protest movement that prefigured similar occupations around the world, including the Occupy movement in the United States. On March 29, 2012, a nationwide general strike erupted into massive street-fighting in Barcelona, as participants wrested control of the streets from riot police. How did this come to pass, and what can it tell us about what will follow the occupation movements outside Spain?

Here, our Barcelona correspondent provides extensive background on the riots of March 29, tracing the trajectory from the plaza occupations to the general strike, and explores the questions that have arisen as anarchists face new opportunities and challenges.

The History

“La rosa de foc ha tornat!” This was the expression of excitement on many people’s lips during the general strike throughout Spain on March 29, 2012. While the unions estimated an impressive 77% turnout, it was the fires blackening the skies over Barcelona that everyone talked about.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, when more anarchist attentats and bombings were carried out in Barcelona than in any other two countries combined and dozens of churches and police stations were burned to the ground, the city was affectionately known as la rosa de foc, “the rose of fire.” The period of “revolutionary gymnastics” in the ’20s and ’30s foregrounded the city as a laboratory of subversion for anarchist struggles worldwide, a role that was taken further with the revolution of July 1936. The struggle of Catalan maquis—guerrillas—during the Franco years was the precursor to the guerrilla struggles that blossomed in Europe and Latin America in the ’60s and ’70s; in some cases, it was the vector along which experience and materials were directly passed on. But this history has largely been lost, thanks to the rupture imposed by fascism and democracy, and Barcelona lost its significance on the revolutionary stage.

With the backing of the democratic powers, forty years of dictatorship and repression effectively suppressed the anarchist movement in Catalunya and the rest of the Spanish state. A great deal of pro-anarchist sentiment remained, but this was dissipated when the rebounding social revolution was sidetracked by the transition to democracy in the 1970s. Hundreds of thousands of people were taking the street, hoping to pick up the torch that had been dropped in ’36, but the government played its cards well, the returning CNT played its cards poorly, and democracy carried the day. Since then, the city has been tamed, if not outright pacified, and the rose of fire forgotten.

Fierce neighborhood struggles continued into the ’80s, but these were largely limited to marginalized immigrant1 neighborhoods and they were calmed by the political and economic integration—or bulldozing—of the slums and shantytowns that gave them birth. In the ’90s, there were several intense squatter and antifascist riots, but the media successfully spun these as isolated phenomena. In the ’00s, social control and pacification made great leaps forward. A new police force trained in democratic policing tactics, the mossos d’escuadra, were introduced along with an insistent public campaign of civic behavior ordinances; in time, the riot disappeared along with street-fighting know-how, the use of Molotov cocktails, and the practice of resisting evictions. The police became untouchable: they only had to charge—or simply draw their batons—to send people scattering.

A combative spirit was still widespread, at least among anarchists, some squatters, and a part of the Catalan independentistes,2 but the tools needed to express it were lost. In 2007, when police tried to win undisputed control of the streets once and for all by kettling and shutting down any non-permitted protest, the so-called antisistema3 halted this by seeking broader alliances, returning to the streets, and emphasizing the contradiction between the State’s attempted power grab and its democratic narrative. This persistence achieved some results, but no one could figure out how to go back on the offensive.

When the economic crisis eroded the public welfare that had guaranteed the social peace, many more people besides the couple thousand antisistema began to take action. Neighborhood assemblies formed, pushed forward by well-meaning reformists, indepes, or closet libertarians, and attracting a few Trotskyists and similar types. The anarchist CNT and the anarcho-reformist CGT, kept in shape by minor labor struggles in a supermarket chain and among the bus drivers, geared up for a battle more worthy of their history.4 The indepes, irked by years of irrelevance despite strong public support for independence from Spain and reenergized by the emergence of a new political party that has not yet entered government to betray them, also made ready for a new offensive. And the black bloc anarchists, finally ready to take the initiative after years of action-repression-prisoner support, moved from the limited field of clandestine action, antisocial propaganda, and self-organization within autonomous ghettos to a more porous terrain on which the skills they had honed could have greater effects.

Barcelona General Strike, September 29, 2010

The general strike of September 29, 2010 was called by the major unions (CCOO and UGT) along with the smaller unions like the CNT and CGT. But a large part of the organizing was also carried out by neighborhood assemblies, non-union anarchists, indepes, and others. On a national level, it was a success from the union standpoint, achieving majority participation despite being the first general strike in eight years. In Barcelona, it was also a success from an insurrectionary standpoint, precipitating an intense riot in which attacks on agents of government and capitalism generalized. The rioting was largely spontaneous, carried out by many more people than the usual suspects, and reached a scale and intensity not seen since at least the la Cine Princesa riots in 1996.5 A large number of arrests with serious charges and an intense campaign of demonization via the media conditioned future actions and attitudes. Nonetheless, September 2010 left diverse actors with more strength and social backing.

Banco Español “discredited” after the general strike of 2010

CCOO and UGT immediately went to the negotiating table and traded in a large part of that backing for the privilege of signing on to the Socialist government’s pension reform. Both unions were in true form. UGT had been a major force in hampering proletarian struggles in the ’20s and ’30s; they were the mass organization that gave the paltry number of Stalinists in 1936 the cover they needed to sabotage the revolution. CCOO (Comisiones Obreras, Workers’ Commissions) is the institutionalization of the libertarian communist Workers’ Autonomy movement of the ’70s. When the fascists who became the Popular Party were looking for leftists to invite into government to help them forestall revolution by putting on a democratic mask, they found their men in the CCOO and the newly reformed Socialist Party (PSOE).

On the other side of things, the CGT (a split from the CNT) and the two CNTs (another split) got over their age-old enmity and started working more closely. Squatter and black bloc anarchists also started working together with CNT anarchists or joining the neighborhood assemblies and working with indepes, closet libertarians, and community activists. Widespread isolation, as much the result of a shared social condition as of any particular choices, began to melt away.

In January 2011, these latter groups decided to organize another general strike without the two major unions. Most people regard this second strike as a failure on account of the low level of participation. This frames the purpose of a strike through the quantitative, organizational mentality of a union. The historical significance of the January strike was to demonstrate that CCOO and UGT were losing their hold. It showed that those operating from a more insurrectionary logic could seize the initiative, cause a significant disruption, and communicate radical ideas if they were willing to work beyond narrow affinities and address the immediate concerns of livelihood usually monopolized by reformist discourses. This discovery is at the heart of two tensions that recur throughout the history of the events of March 29. These tensions have to do with how the principle of affinity changes its behavior between times of isolation and times of coalescence; and how immediate concerns are frequently paired with reformist methods, and idealist concerns with revolutionary, methods, creating a false polarization. This will be explored further in the final section.

After January 27, 2011, the next significant date was May Day, when the anticapitalist protest comprised of black bloc anarchists, the CNT, and many indepes marched from Gràcia to the rich neighborhood of Sarrià, where they smashed a hundred banks and luxury stores before police managed to disperse them. May Day 2011 demonstrated the strength of this new encounter between previously segregated sectors of antisistema. People still did not have the power to withstand the police, nor had they regained street-fighting know-how, but they did manage to go on the attack. For years before 2011, black bloc anarchists in Barcelona had been trying to regain May Day as a combative holiday, failing every time despite creative and varied attempts, while the CNT anarchists had been content with peaceful marches commemorating a waning history. The success in 2011 was an important breakthrough. It also revealed a fear that anti-capitalist violence against the rich would resonate widely, as the media suppressed most news or imagery of the protest.bus drivers, geared up for a battle more worthy of their history.6

On the other hand, criticisms by some fellow protestors demonstrated that these new relationships would be lost if the hooded ones used heterogeneous, multitudinous spaces instrumentally as a mute and convenient terrain apt for wreaking havoc and nothing else. The specific criticisms were not pacifist, nor were they coming from people who were displeased by the smashing up of a rich neighborhood. They had more to do with who bore the brunt of the repression, who held the line against the police, and who carried out the smashing; or with sticking to joint objectives, or sharing information so others wouldn’t be unprepared for a confrontational situation. Nonetheless, after years of dealing with a broad public rejection of their violence, the more insurrectionary of the antisistema were predisposed to ignore these criticisms.

Shortly after May Day came the plaza occupation movement of May 15. How 15M developed in Barcelona and how the democrats had to mask themselves simply to participate in their own creation demonstrated the influence of anarchists, well beyond their numbers. Politicians were not allowed. The practice of open assemblies and the idea that “no one represents us” generalized. Every group and organization had to pay lip service to decentralization, horizontality, and mutual aid, and a number of new groups and activities practiced them. A rapidly growing minority in the movement shifted from seeing the media as allies to responding with criticism, disgust, and even physical attacks. Pacifist hegemony was defeated in a matter of months. Neighborhood assemblies experienced a quantum leap, growing from six to over twenty, with participation swelling from dozens to hundreds and moving from indoor locations to central plazas in every neighborhood. A few neighborhood assemblies even allowed the autonomous direct action of participants and practiced pluralistic rather than unitary decision-making, thus surpassing the petty authoritarianism of direct democracy.

Madrid, May 20, 2011

Protests became so common, along with the practice of marching in columns from every neighborhood to the center before the start of a protest, with even a group of fifty being able to take over a major street, that police stopped trying to contest non-permitted protests. Solidarity and prisoner support became shared responsibilities as thousands of people, including entire neighborhood assemblies, mobilized when those who would previously have been isolated as antisistema were arrested for assaulting politicians. Multiple neighborhoods started “mutual aid networks” based loosely on a model developed by anarchists in Seattle and Tacoma, and the first of these, in the neighborhood of Clot, made waves throughout Catalunya by organizing the first resistance to a mortgage eviction that physically contested police.

Some people only changed their terminology, but on the whole practices were changing. Though many new people did start to call themselves anarchists, anarchists remained a small minority, but an influential minority.

Anarchists spread out over a broadened terrain, often fighting alongside new friends in the neighborhood or the workplace. At the same time, they increased internal communication through debates and assemblies, sharpening their practices, sharing ideas, and building a sense of common strength. Although some anarchists desired unification, most did not, and the anarchist space remained fragmented yet communicative. Most coordination was spontaneous—on the basis of shared information rather than joint planning.

This was never a smooth process. Anarchist principles were hugely influential, but anarchist arrogance often prevented further cross-pollination. The critique of recuperation—of reformist activists and institutions neutralizing social struggles—was widely held among anarchists in Barcelona; in the ’90s and ’00s, even the CNT had been accused of this by other anarchists. The majority of Catalan libertarians have never considered themselves part of the Left. But now anarchists were discovering an undeniable value in working with people of a reformist bent, or whose vision of revolution tended towards recuperation.

It was hard to decide whom to work with, how to argue against a reformist position without shooting the messenger, how to navigate a situation in which anarchists suddenly had a lot of influence yet our cherished principles depended on others to be put into practice. Many anarchists changed in the course of these experiences, but few could be heard to admit how much they had learned from contact with other people or how necessary the struggles of non-anarchists were to the contradictory, chaotic whole. On the other hand, it suddenly became less cool to be openly arrogant, and many anarchists criticized their comrades and themselves and called for more humility. A few argued that sincerity is more important than affiliation or political affinity in choosing whom to work with.

At the end of February, 2012, there was to be a four-day-long public transportation strike in Barcelona. The workers’ leaders—those who spoke loudest and most eloquently in their assemblies—called for major disruption and joint struggle between metro workers, bus workers, and users—that is, everyone not rich enough to have a car. Their proposals were widely applauded and voted into effect. Given that the CGT was one of the largest unions among the bus drivers, and supporting a bus drivers’ struggle had gone well in the past, most anarchists decided to throw themselves headlong into efforts to support the strike.

Despite the popular support organized in neighborhood assemblies and other spaces, the transport workers wavered as the media mobilized a fictitious public disapproval to condemn the strike. Shortly before it was to begin, union bureaucrats played dirty games, and workers reneged on their promises, made private deals, and abandoned those from whom they had demanded solidarity. The strike never got off the ground, and the effort was a major failure. Some comrades took this as a sign to be more cautious, others as a warning to be more uncompromising. Significantly, it became apparent that many anarchists, like the Trotskyists and socialists, did not see themselves as protagonists in the strike—as users who had been in struggle for months already against fare hikes—but as allies to a struggle that was not their own. On one hand, this view masked a populist failure to criticize a clear betrayal of solidarity. On the other hand, it demonstrated an openness to self-criticism among those who had approached a reformist struggle simply for the opportunity of confrontation it presented. The episode also raised the question of the legitimacy of decisions made in assemblies and how seriously to take them, seeing as people will vote one way after a rousing speech, then the other after a week of bad press.

The failure of the transport strike would have been demoralizing, just one month before the general strike so many people were hinging their hopes on. But unexpectedly, the Wednesday of that same week, a minor but important riot broke out in a student and teacher demonstration held during a day-long strike in the universities. The riot raised morale and sent an important message about the source of resistance. It spread as student leaders who had controlled and pacified past movements in the university were effectively silenced—the microphone literally snatched out of their hands by libertarian students—and rowdy students, many of them uninvolved in anything resembling politics, went wild while many others gave symbolic support or flocked towards, rather than away from, zones of conflict. In the aftermath, spokespersons for the platform against the privatization of universities were obliged not to condemn the rioting, knowing they would face a critical loss of support.

Finally, CCOO and UGT called a general strike for March 29. Smaller regional unions in Galicia and Euskadi had already called a strike for that day, and the two major unions signed on to make the strike general and countrywide. CNT and CGT, unwilling to strike on their own after the experience of January 27, quickly followed suit.

CCOO and UGT were essentially forced into this. Ever since the previous summer, as the dwindling 15M movement fumbled about for effective targets and tactics and the rich and powerful continued in their onslaught, everyone had been talking about the need for another general strike. The unions dawdled, explaining pedantically how difficult it was to pull off. Finally, as the joke goes, President Rajoy produced it accidentally in January when, at an important Eurosummit, he told the Dutch and Finnish prime ministers how good and “aggressive” his new Labor Reform was, how it would make it much easier to fire workers, but it would “cost [him] a general strike.” He did not know that his microphone was on.

The strategy of the major unions was to sabotage their own strike. People had months to prepare for the general strike of September 2010, so they could make their own plans apart from the unions. This time, CCOO and UGT called it less than three weeks in advance. They put up almost no propaganda until a day or two beforehand, letting the media dominate the conversation. Their ideal outcome would be statistically massive participation and a huge turnout to their own protests, without riots or major disorders. With widespread popular anger, it would be almost impossible to bring crowds into the street while keeping things under control, but if they could minimize the opportunity for the antisistema to prepare for disorder and keep their own flocks separate from the rabble in the streets, they could minimize their losses.

Anti-capitalist preparations for the strike took multiple forms. Anarchists worked alongside indepes, socialists, and others in neighborhood assemblies, strike committees, and meetings of workers or the unemployed; or they prepared in their own affinity groups, assemblies, or unions (the CNTs). No one, neither police nor antisistema, could make reliable plans for the day. They could either attempt to impose order, or move within disorder.

The Strike

In several neighborhoods, the general strike began at midnight, with small groups closing down bars and setting off a traca, a long strip of noisy fireworks. In Casc Antic, a picket supposedly connected to the CGT entered a casino as if to shut it down, and made off with over 2,000 euros in cash; the union quickly denied any connection. As a result, the casino unexpectedly had to close the day of the strike and claimed damages of €50,000. Starting around 6:30 in the morning, barricades shut down the major highway and rail entrances to Barcelona: Av. Meridiana; Gran Via; Diagonal; la Ronda Litoral; metro Zona Universitaria; metro Llacuna, and others.

The morning barricades

Starting as early as 4 a.m. in some neighborhoods, and at 7 in others, people convened roving pickets that shut down roads and closed businesses that tried to open—primarily bakeries, bars, and supermarkets. In Horta, 200 people blocked streets, stopped and sabotaged buses, and smashed the windows of the Mercadona, a major supermarket chain infamous for threatening and harassing its workers. In Sants, the picket invaded the train station and beat up a businessman who tried to grab one of the picketers. In Clot, 80 picketers went up and down the neighborhood, shutting down every single street with barricades of dumpsters until riot police attacked, making three arrests. In neighboring Poble Nou, a small picket of CCOO and UGT symbolically blocked a road while the larger neighborhood picket closed shops until the riot police swooped in, chasing the Clot picketers who had taken refuge there. In Sant Andreu, riot police charged the picketers outside city hall, arresting three. In Raval and Eixample, there were morning protests in addition to the pickets.

At 11 a.m., four different neighborhoods met at Plaça Glories to march together to the center, shutting down Gran Via on the way and insulting a small group of CCOO and UGT picketers standing on the sidewalk. There were tens of thousands of people in the center for the “unitary picket.” It was at this point in the September 2010 strike that the riot started, but this year there were more people, and the plan was to march away from the center, towards Gràcia. Unfortunately, major avenues, specifically designed to control rebellion, had been chosen as the most direct route for the march, and the huge crowds advanced slowly in the hot sun, far from the businesses on either sidewalk.7 The result was neither a protest nor a picket. Nonetheless, most businesses in the vicinity closed as a precaution. One luxury hotel that had been collectivized by anarchists back in ’36 was paint-bombed, but generally the atmosphere was tranquil. Early in the procession, some people swarmed the stock exchange and set a trash fire at its front doors, but quickly backed off when the riot police drove up. At Jardinets de Gràcia, the march stopped for nearly an hour, though the column of people still stretched all the way back to Plaça Catalunya.

Then some people with flags and banners finally managed to get the crowd moving, turning off to the left into Eixample. Early on, someone threw a flare onto the eaves of a hotel, starting a small fire. The sight of smoke had a magical effect. The passive, helpless crowd was suddenly transformed, as masks appeared and people covered their faces. Tools came out or were pried from the landscape, and soon every bank and luxury store the crowd passed was smashed. Dumpsters were overturned and set on fire. “But they closed!” an older demonstrator asked in astonishment as a luxury store was smashed, “What are you doing?” Clearly, some people wanted the picket to remain a picket, and did not understand the purpose of going on the attack.

A fire engine moved in and riot vans were seen racing around in the distance; it was later learned that they were pushing back the bulk of the crowd coming up from Pl. Catalunya to prevent reinforcements when it came time to attack the rioters. Many people held back, but thousands pressed forward, smashing more banks and completing a circle to return to Jardinets. At this point the mossos (the Catalan police) attacked, racing forward with riot vans on both flanking streets and cutting off a part of Jardinets. Several people were run over, many more beaten as they ran the sudden gauntlet appearing around them, and a few arrested, although the crowds were so huge that it was difficult for the police to hold the ground necessary to cuff people and drag them away. The largest part of the rioters, mostly anarchists, ducked into the narrow streets of Gràcia, where they could possibly have seized the whole neighborhood and destroyed Gràcia city hall, guarded by only a few police who locked themselves in upon the appearance of five hundred black-clad rioters. But the latter were still in panic mode after the police assault, and they dispersed. Over the following hours of hiding out and trying to regroup, many anarchists remarked on the principal long-term weakness in street situations in Catalunya: people always run from the cops. Elsewhere, in fighting lower down in the city, a group advanced with dumpsters, rocks, and flares without being immediately scattered, but more significant gains were necessary.

At 4:30 p.m., the march of the CNTs, the CGT, and other anarchists convened in Jardinets to march back down to Pl. Catalunya. About 10,000 strong, with at least tens of thousands of people nearby tying up the police, they casually strode down the posh street of Pau Claris, burning dumpsters in every intersection, smashing open every bank and tossing flares and trash inside. The rampage also led to conflict within the march, as some protestors confronted and tried to unmask the rioters. An eerie scene appeared in their wake: onlookers gawking at the ruins, the numerous columns of smoke, and the firefighters passing trash fires five meters in diameter as they raced to put out the burning banks. At the corner of Pl. Catalunya by the Corte Inglés, one of the most important shopping malls in the country, the mossos attacked and set up a cordon to protect the mall.

The anarchists dispersed, most of them joining the immense crowds in the plaza. For over an hour, tranquility reigned, journalists mingling with the crowd filming freely. Then, little by little, youth and hooligans,8 many of them not even masked, began to escalate against the police in the upper right corner of the plaza, throwing trash and setting a dumpster on fire. When the dumpster fire grew so large the police had to pull back their vans to keep them from also catching fire, the rowdy crowd attacked, chasing police an entire block to Plaça Urquinaona. Police made as though to counter-charge and people began panicking and running. This time, those with more street experience calmed the panic and urged everyone to stand their ground and fight back, which the hooligans and some others quickly did. Finally, the necessary tools for turning the streets and sidewalks into projectiles appeared or were created from what was at hand, and the police were pelted with a barrage of rocks. In almost an hour of freedom on a street won by force, hooligans, anarchists, and indepes smashed into and set fire to a Starbucks and a bank, and with an almost sick determination smashed through a glass and then a metal wall to open a back entrance to Corte Inglés and set a fire in the coveted shopping mall, as media and bystanders filmed, some out of curiosity and others as a deliberate attempt at intimidation. A few people also shouted at the rioters, but thousands more applauded and held their ground rather than panicking, running, and leaving them isolated, as would normally happen.

With huge crowds intentionally or unintentionally backing up the rioters, the police could not get around to attack them from behind. Slowly, they advanced under a hail of rocks. When another group of riot police charged up along the Corte Inglés from the lower right corner of the plaza, the crowd drew back and the police regained the entire block that had been taken from them, along with one side of Pl. Catalunya.

But still people did not retreat. They attacked several press vans, stealing a tank of gasoline from the generator in one of them and putting it to quick use. They started improvising barricades and smashing up the sidewalk for more rocks. For what seemed like another hour, police continuously fired a hail of rubber bullets, wounding many protestors. One person lost an eye, another had a lung punctured. A four-year-old child was shot. But people made shields or took cover behind a row of jersey barriers and other obstacles to continue throwing rocks at the police. In most instances, hooligans and immigrant youth were at the front, with a handful of anarchists, and their bravery was inspiring.

Finally, to take back the plaza, the mossos had to use tear gas for the first time in their decade-long history. The gas was not that strong, but as an unknown it provoked fear. The first couple canisters were kicked back, but the next few sent the crowds retreating towards Plaça Universitat, smashing more banks and starting more fires on the way. For the next hour, all the streets around Plaça Universitat belonged to the people, until police were finally able to advance another two blocks. Next, fires broke out in Passeig de Gràcia (above Pl. Catalunya) and Raval (the immigrant neighborhood below Pl. Universitat). In the latter area, immigrants and anarchists set fires all night, set up barricades, smashed banks, and gathered rocks, hoping the police would come. Excepting a few undercovers who were quickly chased out, there was little confrontation, only because the forces of order chose to avoid it. All throughout the city, on the periphery of the major points of conflict, people raided supermarkets, smashed banks, burned dumpsters, and beat up undercovers. Late into the night, firefighters raced back and forth, in the center or on the outskirts of town. For a day, the police lost control of the city, as they had on September 27, 2010; perhaps for the first time since the Cine Princesa riots of 1996—although this time on a much larger scale—a large group of people learned how to push the police back in sustained fighting.

The riot was an event of great significance. The economic shutdown was obvious, even if many shops did not close down. Perhaps a thousand dumpsters were turned into barricades, along with countless tires and other objects. 295 dumpsters were burned, causing the city half a million euros in damages, not counting the streets and sidewalks ripped up, or the many banks and chain stores smashed or set on fire. But the experience of winning the streets was the most significant. In the aftermath, anarchists felt victorious, while the Catalan Interior Minister acknowledged that this was a sign of times to come—an image from the future, as it were. In the buildup to the general strike, no one believed that one day’s actions would solve anything, and this conviction remains even though the strike surpassed everyone’s wildest expectations. But what was gained will be vital for the battles ahead.

The Barcelona Stock Exchange at the end of the day

The Repression

In Tarragona, another city of Catalunya, the antisistema took advantage of the fact that all the riot police were in Barcelona and went on a rampage, burning the offices of several political parties and attacking police cars. The next day, police arrested nine known radicals, from indepes to anarchists, lacking evidence but making up for it with their desire for revenge.

There were a total of 79 arrests in all Catalunya on March 29, 56 of which were in Barcelona. Many arrestees were beaten and injured in the police stations. Two had to have their spleens removed as a result of the beating. At a solidarity protest outside Modelo prison a few days after the strike, the police carried out an arbitrary and particularly sadistic arrest of one demonstrator, removing him from his wheelchair and leaving it in the street as riot cops cleared a path through the angry crowd for the paddy wagon’s exit, breaking a bone of at least one protestor.

Most of the arrested are out on bail or conditional liberty, awaiting trial with serious charges, a process that will take two years or more. Three were denied bail: two indepes who were arrested in the morning with compromising materials, and one of the picketers arrested early in the day in Clot, who is also awaiting trial for harrassing politicians during the siege on Parliament in June. In the most intense moments of fighting, police were rarely able to make arrests, and little evidence exists to connect arrestees to the day’s most flagrant crimes. Nonetheless, the courts understand the political need for exemplary punishment, and they will make the necessary arrangements.

The politicians, meanwhile, are seeking new repressive tools to combat an increasingly rebellious future. In Madrid, the Spanish government is pushing ahead with changes to the penal code, and in Catalunya the Generalitat9 is calling for harsh new measures. The basic characteristics will be familiar to anyone acquainted with repression, and they are summed up by the complaints of Felip Puig, the Catalan Interior Minister, that the law has been too permissive of these “violent ones,” and his appeal to the good citizens of Catalunya to help isolate them. In the first line, the penal code will be changed, with the following probable results: the right to assembly will be limited to prohibit masking and disguises; “public disorder” charges will be expanded to include entering a public institution to protest or blocking access to the same; the minimum sentence for public disorder will be raised to two years, allowing the accused to be held in prison those two years awaiting trial; the charges regarding “criminal organization” will be made more flexible; “assault on authority” will be expanded to include passive resistance to the police; much harsher charges will be given for throwing objects at the police; and sentencing for vandalism will be raised to match sentencing for similar charges under the antiterrorist laws.10 Specifically in Catalunya, the number of riot police will be increased by 25% and a special prosecutor will be appointed to focus solely on “urban violence.” More cameras will be installed in public places and police will increase filming of demonstrators.

In the second line, the Generalitat will set up a website to encourage and facilitate citizen snitching, and perhaps also to set up a mechanism for the crowdsourcing of identifying rioters from photos, as has been done in other countries. They will also attempt to shut down websites, blogs, and Twitter accounts that call for violent protest, and they will ask citizens not to encourage such violence by sharing personal footage of rioting and street-fighting on their blogs and Facebook.11 The media, for their part, will continue to demonize the “violent ones” in hopes of isolating them. And the new penal code will allow prosecutors to charge any organization with a felony for calling a protest that ends in violence.

The anarchists have lost no time responding to this. The two days following the strike, there were solidarity gatherings outside the jail and courts. On April 2, a solidarity protest of about five hundred went from Pl. Universitat to Modelo prison. Less than a week after the strike, thousands of copies of at least two anarchist posters appeared on the walls of the city, justifying the riots. One asked, “What did y’all expect?” while the other proclaimed “The end of obedience!” There is talk of connecting these cases with other recent cases of repression—the arrests from the September 2010 strike, the January 2011 strike, May Day, the Pl. Catalunya eviction, the anti-eviction battle in Clot in July 2011, the eviction of an occupied building in October 2011, the Parliament arrests—for which there are already protests and support actions planned. Coordinated attempts to publicize and oppose the new laws are also in the works.

There are also attempts at criticism and collective learning, as some of the arrests were preventable, and in some cases people precipitated confrontations when it was not wise to do so or when others wanted a safer atmosphere. In Plaça Catalunya, those who wanted to be safer could easily go to the side of the plaza away from the fighting, and in fact there were many families with children or older people in the plaza symbolically supporting those fighting the police. But this was not possible in other spaces, nor would there have been promising opportunities to attack the police even if everyone had wanted to.

These criticisms are much easier to understand and act upon now that the pacifist back-stabbing that arose with the 15M movement has been surpassed. And it seems that anarchists, rather than denouncing such concerns in unwavering pursuit of constant confrontation—a strategy that has already been tried here and abandoned—are willing to listen and change their ways, following good experiences working with the people making those criticisms. Any change would not be towards pacification, but towards the blending of different spaces and forms of struggle, in order to assume the offensive in ways that do not endanger others and that can spread.

The lessons learned

The events of 29M hammered home a few important lessons.

When it comes to street-fighting, some observations stand out more immediately than others. The most fundamental precondition for action isn’t having a plan—as plans always fall apart in these situations—nor coming materially prepared, although that doesn’t hurt. The most fundamental need is the ability to push back the police. Those who win a space directly from the police can subsequently do everything. The ability to beat the police comes down primarily to attitude, secondly to experience, and thirdly to materials. The first two can produce the third from the urban landscape, if no one has prepared them in advance.

Those who were most effective in pushing back the police were young people from a mix of socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds with little or no prior street experience. Their effectiveness was multiplied when people with more experience and preparation joined them. Likewise, anarchists who fought alongside them accumulated more street experience in one day than in the preceding year of protests. Experience does not accumulate passively. It only accrues to those with attitude.

Less apparent is the importance of those who were not on the front lines. The sine que non of the March 29 riot was the crowd physically and emotionally backing those in the thick of the action. The forms and intensity of this support must be diversified and increased, a need that is inhibited by the idea that anarchists either fight on the front line or run away. The anarchists in the third line raising their hands and telling people to stay calm are equally important, along with those farther back breaking the pavement into projectiles—too often, the latter activity is carried out on the front line, where people and the piles of stones they accumulate are more vulnerable. It is also necessary to have comrades who do not participate in the fighting, but who argue in favor of it against those who try to pacify or isolate the rioters, and others farther back in the areas safer for children or old folks, who applaud the fighting or cheer every time a new fire breaks out, and who encourage people not to abandon the fighters, but to see them as “ours.”

“Against the aggression of the rich and their politicians: self-defense”

Winning the support for this kind of street-fighting was a gradual but steady process after the mass emergence of pacifism in the 15M movement. In many ways, that movement was structured to be an assault on the memory of struggle here, and many people, from indepes to anarchists, had an interest in recentering that history in the new movements, as it had been centered in the trajectory of struggle from the 29S general strike to May Day 2011. This legacy is the vessel of a deeply rooted anti-capitalist analysis and a combative practice. Together, these two aspects of popular history legitimize radical struggle and the actions that must accompany it, highlighting the superficiality of pacifism and democratic populism.

In the first weeks of the plaza occupations movement of 15M, anarchists repeatedly had to argue against pacifism, distribute fliers and texts, and justify every minor detour from the most tamed and civic forms of activity. Police violence hastened this learning cycle. In all the subsequent major demonstrations, anarchists identified the point of conflict and tried to push it forward, emphasizing visible rather than clandestine actions. For the first few months, the point of conflict was graffiti. Nearly everyone had already assumed the technically illegal action of seizing the streets for every single protest, but if people masked up and started painting banks during a protest, others in the crowd got angry and even tried to physically protect the banks. For every two people who painted, five more were needed to defend their actions and sometimes physically protect them. Protest by protest, fewer people objected to political graffiti—provided it was directed at banks, government buildings, and other hated institutions—and more people in the crowd argued in favor of the spray-painting. The significant action was not the vandalizing of a bank, but the popular debate that came to legitimize it.

The next point of conflict centered around masking up. By October, hardly anyone criticized spray-painting in demonstrations, but argued you should do it without a mask. Again, anarchists defended the practice and distributed literature about it, but masking was less likely than spray-painting to generate an open conflict, so there were fewer opportunities to engage. Around this time, the police arrested people who had been caught on tape harassing politicians during the siege of parliament in June, so it became easier to explain the practical reasons for masking up, even as the media flooded with rhetoric about the cowardice of masking up. Fortunately, the practice easily communicates itself on a visual and stylistic level, especially among the youth; but in Barcelona it still creates a rupture between those who automatically sympathize with the practice and those who are automatically turned off by it.

In other demonstrations, people introduced more offensive tactics by paint-bombing especially odious targets such as the Stock Exchange and political party offices. Outside of the space of demonstrations, on random days in random neighborhoods, hooded ones appeared to smash a bank and quickly disappear again, creating another possibility for the normalization of attacks. But before this process could continue further, it suddenly accelerated with the student riots and then the general strike. On the one hand, these events normalized combative popular resistance, giving more people a chance to participate. On the other hand, they allowed those sympathetic to such attacks to quickly accelerate and break away from those inclined to condemn the violence. While a few thousand people might be able to win in the streets for an hour or two, in the long run if such a group does not continue to expand and undermine the barriers of legitimacy placed around it, it will inevitably be isolated and pacified. Nonetheless, by the time of the strike, a large part of Catalan society had been accustomed to low levels of street conflict and property destruction, and the worsening prospects for the future gave some of them the rage to support a sudden escalation of this conflict.

Spectacularization—the practice of reducing action to images—is a strong force for isolating rioters. While opposition to the press and awareness of the need for protective measures are slowly spreading in the form of attacks on journalists and efforts to convince bystanders not to film, there is still a dangerous degree of spectacularization during riots. The spreading of new chants, an effective tactic in the radicalization of 15M and the struggle with pacifism, has also been used against the media; one couplet, “The press aims, the police shoot,” has become popular since October. However, there is not yet any chant against filming by ordinary people, although some propaganda has been distributed on the subject. Nonetheless, if journalists can be pushed out of protests and come to be understood as equivalent to the police, the most dangerous forms of spectacularization will be eliminated.

It is also necessary to take a step back from the exigencies of street-fighting to ask what was accomplished and what the point was. The most important elements of the conflict were emotional and symbolic, not economic. The State, itself the source of currency, cannot be destroyed by economic losses but only by popular attack. If CCOO and UGT had achieved 2% higher participation in the strike and prevented any riots and property destruction, total economic losses would have been far greater, yet social struggles would have gained nothing. What was gained was the interruption of the narrative of social peace that is vital to governance, the temporary spread of participation in outright resistance, and the experience that will make it possible to surpass this rupture in the future and to create relationships with the strangers who became our comrades for a day.

This latter activity is rarely attempted, even though it is one of the most promising opportunities such insurrectionary moments offer. Anarchists live in the same neighborhoods as the hooligans who led the fight against the police, but they are totally alienated from one another as long as there is no riot going on. People who engage in street-fighting should not be idealized, but many of them suffer police violence on a daily basis, and at least some of them have strong anti-authoritarian tendencies. Anarchists should approach them and others as people we will live alongside and participate in assemblies with after the revolution.12

In order to bring that revolution nearer, it will be necessary to surpass the natural divide between night and day, learning to sustain riots over multiple days. Only when they extend in time will they have the possibility of growing into an insurrection that extends from city to city. Otherwise, they will serve merely as an emotional release. In the meantime, when normality returns, the question is how to build off what was won, how to access the collective experience of the riot and prevent the social pendulum from swinging towards reaction.

Only the last part of this question is answered within the collective body of knowledge: support the repressed; build relationships across the divides imposed between good and bad protestors, and between protestors and spectators; counter the media backlash by highlighting the role of the media in the social war; and oppose new repressive measures legislated by the State.

The Strategic Tensions

Historically, the anarchist movement in Catalunya has constructed its identities more around shared practices and locales than unifying ideologies. It is inaccurate and inappropriate to speak—as distant spectators tend to—of insurrectionary anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists as two opposed and distinct groups. These ideologies exist, but as a fluid interchange along with other positions, rather than as opposite poles. They are more practice than ideology.

Until the end of July 1936, when it became a class-collaborationist and ultimately statist organization, the CNT was without a doubt the most important revolutionary organization in Spain, but it functioned in equal parts as a union and as a pole for the construction of informal combative neighborhood networks.13 Important figures within it ran the gamut from insurrectionary to syndicalist, and the exodus of the latter was an important step in its radicalization. Cenetistes14 fought for libertarian communism, collectivism, and cooperativism, or they simply fought against present conditions, not knowing what could come next. Many militants changed their position and practices depending on the fortunes of the social struggle, so that the most insurrectionary in one moment would be the most moderate in another moment, as in the case of Garcia Oliver. Ascaso and Durruti, perhaps the most principled of the most influential members, were both committed syndicalists—insofar as they saw the union as an important tool for workplace agitation and organization—and insurrectionists, as they believed the time for attacking and thus building the capacity for armed struggle was always at hand; they had argued and practiced this in the ’20s, at a time when most thought it more prudent to wait. At times, their practices coincided heavily with the individualist, illegalist anarchists who often made their base in the Raval; at other times, they seemed like pure union militants.

To give another example, probably the most important anarchist social center formed in Barcelona in the years before ’36 was the appropriately named L’Ateneu Eclèctic.15 It would not have passed the censor with the more traditional descriptor of ateneu llibertari, but the adjective “eclectic” was equally accurate. As Abel Paz, the anarchist historian from the same neighborhood (Clot) would later write, it was a social center where pacifists mingled with practitioners of propaganda by the deed; where an influential anarchist individualist held study courses alongside the libertarian youth group or CNT militants who carried out propaganda or sabotage in the nearby textile factories; the home base for the large anarchist collective Sol i Vida, which practiced vegetarianism, nudism, free love, and excursions to the mountains to practice with firearms, and a formative space for the Barcelona group of Mujeres Libres.

Nowadays, anarchists in Barcelona typically denominate themselves with imprecise caricatures (els black bloc, els refors, els hipis) or with references to a locale such as a neighborhood or social center, whose participants are diverse and change over time, but the conglomeration of which contributes a particular character. In this way, they fulfill the inevitable need of having to name themselves and one another, and they do so in a way that is prone to stereotyping and even disrespect, but also flexible and blurred, allowing individuals to move easily between labels and thus also facilitating debate between different groups rather than rendering difference as a competition between irreconcilable ideological opposites.

One of the two CNTs is jokingly referred to as a syndicate of insurrectionaries, whereas some “black bloc” anarchists hold ideas about unity, formal organization, and technological civilization that would make anglophone insurrectionists shudder. Almost every anarchist in Barcelona today recognizes the importance of the CNT in building the revolutionary movement that made July 1936 possible; they also blame the CNT for the revolution’s failure. Most of the anarchists outside of the CNT blame that organization’s dynamics for the loss of the revolutionary opportunity during the transition to democracy in the ’70s, while cenetistes are more likely to acknowledge some errors but blame state repression. Italian insurrectionary anarchism, brought to Spain by the Córdoba bank robbers in 1996, found its most active adherents among the FIJL, the youth organization that subsequently split from the CNT. The CNT’s position, denying support for the bank robbers, also caused many others to leave, but some who left have subsequently rejoined, and its character has changed over the years.

In the aftermath of the strike, the CNT of Sabadell (a city just outside of Barcelona) released a statement criticizing the Barcelona branch of the CGT for distancing itself from the riots and speaking of good and bad protestors. The title of their communiqué was “Against the System, Its Defenders, and Its False Critics,” a direct reference to the insurrectionary classic, At Daggers Drawn.

The strategic tensions that manifested throughout this long history of 29M do not signify a contest between two ideological poles; readers who attempt to mine the account to further such a contest will be missing the actual conversations happening among comrades in Barcelona. The points outlined here have arisen in local debates; they are based in present needs rather than abstract competitions.

The principal strategic tensions alluded to above have to do with unity and engagement. One important theoretical dispute is between anarchists who see unity as a goal and those who do not. In times of isolation, this tension is unlikely to arise; both those who prefer to work in affinity groups and those who prefer to work in popular or open groups will have few options regarding what spaces to operate in, and the projects of one type of group will likely appear irrelevant to the projects of the other. Those preferring different approaches will likely dismiss or ignore each other, while internally, tendencies towards disunity will usually be overcome by the need to work together because of the scarcity of potential comrades.

In times of high momentum and coalescence, these different approaches can meet and overlap, while many more potential comrades appear. In this new dynamic, some anarchists will feel that difference is creative, while others see it as disorganization. Some will believe that fragmentation is a natural property of non-coerced groups, while others will believe that greater affinity is the natural result of working together. Some will seek to maximize the range of possibility, creating a chaotic social struggle, while others will seek to coordinate and unify, producing a disciplined social struggle—or, lacking the force or common identity to instill discipline, an organization that attempts to encompass or represent the entire struggle.

The other theoretical dispute results from the erroneous association of reformist practices with addressing immediate concerns on one hand and revolutionary practices with adhering to abstract ideals on the other. In times of low social struggle, it is easiest for anarchists focusing on immediate concerns to adopt reformist language and practices, and for anarchists committed to revolutionary practices to frame their action in terms of long-term ideals. When a wider range of people start talking about immediate problems in more angry, uncompromising terms, some revolutionary anarchists will jump to the opposite pole, suddenly talking about immediate problems—and forceful, perhaps even revolutionary solutions—without expressing their long-term desires and radical analyses.

The others, meanwhile, will disdain popular struggles and further withdraw towards purely anarchist projects. Bringing uncompromising anarchist ideals to the complexity of immediate problems is the most difficult option, and thus the most rare.

Both of these tensions have everything to do with moving from an antisocial position to a populist one. This is fundamentally an error of not transcending the limitations—both chosen and imposed—of a period of social isolation, instead fleeing towards the easiest, most superficial practice of communication when new convergences make this possible. Anarchist populism is the result of comrades abandoning the good instincts but preserving the bad habits of the antisocial position.

In the sort of coalescence experienced in Barcelona between 2010 and 2011, anarchists faced a changing environment and they inevitably changed with it. Everything they gained, they gained through an instinct or a strategy of engagement, exploring new spaces of protest and intervening in heightened social conflicts. Anarchists have influenced the ideals and practices of the new social movements out of all proportion to their numbers. Many errors, meanwhile, stemmed from the limits of populist or antisocial tendencies. The possibility remains that anarchists will remain outside these movements, left behind as reformists steer them towards institutionalization, or that anarchists will lose themselves in these movements, abandoning their principles for fear of being marginalized. These two errors are simultaneous and complementary.

After the September general strike and the 15M movement, anarchists recognized the opportunity to work in much larger groups, and these were the tightropes they had to walk. At the beginning, 15M had the appearance of a broad social awakening. As most participants found no means to continue in that direction and returned to the barbituates of normality, the wave receded, but the previous formations of social struggle had been left in disorder. They were more populated, more numerous, more heterogeneous, and more entangled.

Reacting to the inevitable decline in the social movements that had suddenly expanded during the summer of 2011, and the fact that new spaces of protest and action were still much larger and heterogeneous than before—and thus, in a conservative logic, more susceptible to dwindling and factionalizing—some anarchists exhibited a populist tendency. Fearful of losing their newfound support, they downplayed their anarchist identities and sought greater unity on the basis of necessarily watered-down anti-authoritarian analysis. Other anarchists fortified their antisocial position, convinced that participating in these new heterogeneous spaces would require compromising their principles, as seemed to be the case with their populist comrades.

The anarchist space of Barcelona is fragmented and communicative. It is neither unified in a single organization or identity nor segmented in isolated, non-communicative scenes. Fragmented and communicative anarchist spaces tend to be particularly potent in developing new practices and adapting to changing circumstances.

Anarchist propaganda around the recent general strike was less openly anarchist and accordingly less radical. Many problems and principles that are important to anarchists have been almost entirely left out of recent anarchist propaganda, at a time when more people than ever are open to radical ideas, and drastic proposals are necessary. Missing this opportunity, many anarchists have focused on single-issue propaganda that emphasizes the immediate problems of normal people: work, healthcare, housing, education, the police. They trace these problems back to capitalism and the State, but in a way that encourages a critique based in convenience that could disappear as soon as someone lands a good job. The tendency has been more to avoid isolation than to push the envelope. This tendency may foil repression, but the relationships it creates and the critiques it spreads are likely to be superficial.

Other anarchists have withdrawn to publications and actions intended strictly for themselves and other anarchists. Some have produced propaganda that criticizes the disappearing welfare state in a way that mocks the hardship people are suffering because of this disappearance. Nonetheless, this position also fosters a certain strength and independence of action that probably deserves some of the credit for the victory in the streets.

These tensions are unresolved, and they constitute more of a balance than a contest. How do we share radical critiques of this society without scaring away other members of it? How do we participate in heterogeneous spaces without facilitating our own recuperation? How do we counteract the narrative the media attempts to impose without ceasing to be dangerous to the established order?

In any case, anarchists have more and stronger relationships now than two years ago, and are armed with more potent experience. Debates are ongoing; already, there are attempts to confront the criminalization carried out by the State in the aftermath of the riot, and to distill the lessons of that day of spontaneous fury.

New innovations will likely arise as comrades in other countries prepare for their own general strikes, and those innovations might find their way back here. Perhaps the tremors of disorder generated in Barcelona will help shake off the illusion of stability that still reigns in other countries, showing the whole world that it is not the rioters in the streets who are surrounded by the forces of order, but the ruling classes who cling to disappearing islands amid a swelling sea of rage.

Appendix I: A Clarification on Influential Minorities

The key difference between an influential, insurrectionary minority and a vanguard or a populist group is that the former values its principles and its horizontal relations with society and tries to spread its principles and models without owning them, whereas a vanguard tries to control them—whether through force, charisma, or hiding its true objectives—while a populist group offers easy solutions and caters to the prejudices of the masses in fear of being isolated. The populist group never actually overcomes isolation, as that would require forming strong relations that can abide a difference of opinion. Instead, it simply mimics the mass.

Because they both seek the warmth of the herd, the vanguard and the populist often become bedfellows, as the Stalinists and the UGT did during the Spanish Civil War. Within this partnership, the former will be more effective and will make use of the latter.

The influential minority, meanwhile, is prone to developing an antisocial tendency—as its idealism contrasts with the unprincipled pragmatism of the majority—and becoming accustomed to the role of gadfly. If this tendency manifests as a disdain for the rest of society and a commitment to realizing its principles despite and against the masses, it is likely to find common ground with vanguardist groups, who will probably use it as shock troops for carrying out offensives—as in the October Revolution. If, on the other hand, it takes the easier antisocial path of abstracting its principles, it will limit its influence, because nothing around it will reflect its ideals or invite its engagement. Only when they constantly relate their principles to the complexity of their surroundings can such minorities serve as a model for others to become actors in their own right.

The influential minority works through resonance, not through control. It assumes risks to create inspiring models and new possibilities, and to criticize convenient lies. It enjoys no intrinsic superiority and falling back on the assumption of such will lead to its isolation and irrelevance. If its creations or criticisms do not inspire people, it will have no influence. Its purpose is not to win followers, but to create social gifts that other people can freely use.

Appendix II: Propaganda Archive

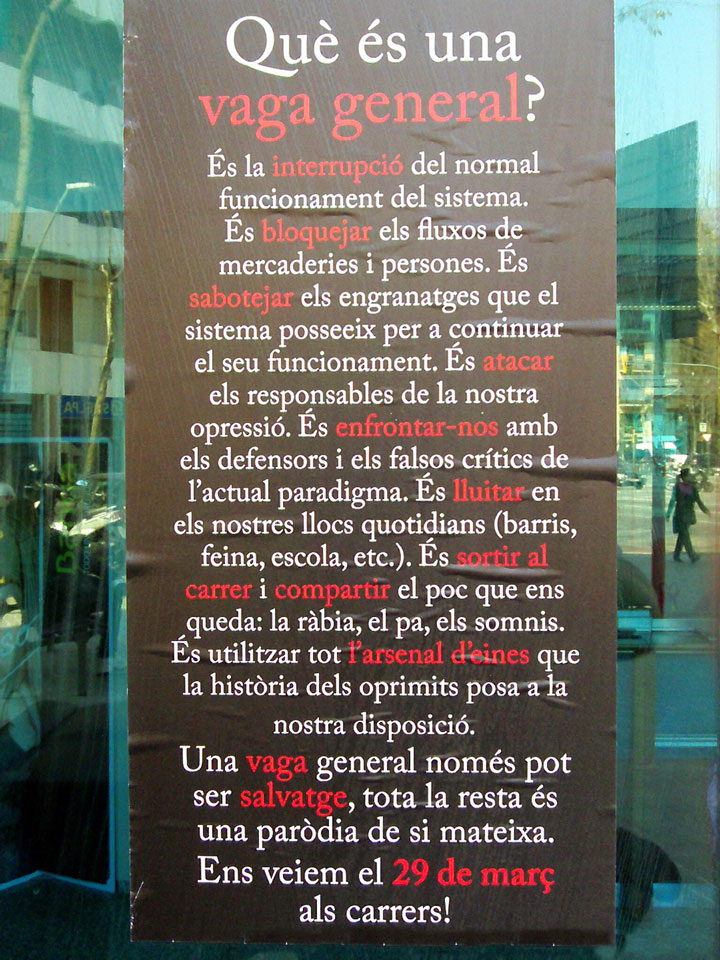

Text of an anarchist poster put up before the strike

What is a general strike?

It’s the interruption of the normal functioning of the system. It’s blocking the flows of people and merchandise. It’s sabotaging the gears necessary for the system’s functioning. It’s attacking those responsible for our oppression. It’s confronting the defenders and false critics of the current paradigm. It’s struggling in our daily spaces (neighborhood, work, school, etc.). It’s going out into the streets and sharing what little we have left: rage, bread, and dreams. It’s using the entire arsenal of tools that the history of the oppressed has put at our disposal.

A general strike can only be wild, all the rest is self-parody. We’ll see each other on the 29th of March in the streets!

Text of a flyer distributed to youth before the strike

They’ve snatched away your future. The superficial welfare, the American Dream they imposed on previous generations is something they can no longer promise you. No diploma, no healthcare, no mortgage, no career, no car, no retirement, no iPod, no ski vacations. Forget it all. Now they are saddling you with the following future: a merciless competition between those who manage to attain a stable job as cops, bankers, metro guards, managers, or engineers, and those who will have to live going from one precarious, short-term job to another, handing out publicity flyers, cleaning up after tourists and rich people, working as waiters, cashiers, whores, cooks, metal scrappers, busting your ass working in construction or messing up your eyes working behind a screen. In other words, the bastards without a conscience who want to work as mercenaries, scabs, or exploiters will triumph and everyone else will be left without retirement, healthcare, or a salary.

Take a good look at your friends. Which of them would kick you out of your apartment for not being able to make the rent? Which of them would lock you up in prison for stealing or selling drugs as a matter of survival? Which of them would fire you just to increase their profits? They’re the ones who will take over the world and control your future, while all of you who are honest, solidaristic, and humble are gonna get fucked.

They’ve destroyed the world you will inherit. They’ve poisoned the water and the air through their greed and disrespect for nature. They’ve cut down the forests to turn them into commodities. They’ve fucked the climate out of pure caprice and arrogance. They’ve contaminated our minds with an authoritarian, pedantic education and a stupefying culture. They’ve stolen our knowledge of how to feed ourselves, heal ourselves, build our own houses, and resolve our own conflicts so that we remain dependent on their wage labor, their police and their justice, so that we only have to learn how to serve them, obey them, and use the machines they force on us rather than our own tools. They’ve made history disappear so we don’t understand how this happened, how we lived before capitalism, and how we could live in our own future, created by us and not by them, that greedy pack of exploiters, authoritarians, torturers, and murderers.

This disappeared history is the history of our resistance, our struggle against all authority, and therefore it constitutes the seed of a future without them. But if they destroy the entire world, if they convert it into an uninhabitable place where we will be perpetually dependent on their technology and their control, there won’t be a future for anyone.

Burn it, then. Burn the future they’ve assigned you. Burn the plans they want to impose on you. Burn their inhuman authority, burn their false wisdom. Burn everything that is a lie to create the possibility, however improbable, that the seeds of a new world sprout from the ashes of this one. And don’t trust in anyone except for your friends, those who prove to be solidaristic, those who feel rage. And when they call you “violent,” when they call you “senseless,” when they demand you stop or attempt to recruit you, it’s because they’re afraid of losing control, of being revealed as nothing but authoritarian idiots who have destroyed the world and the future.

Burn it all, to start anew, and without them.

To the indefinite strike, to the recovery of sabotage, fire, vengeance, and permanent revolt.

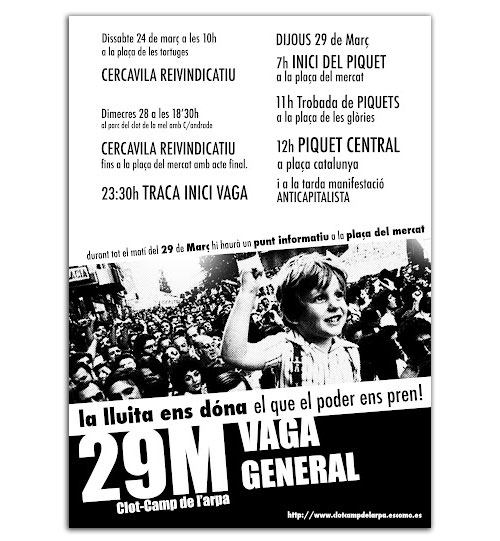

“The struggle gives us what power takes away!” A poster from one neighborhood calling for the strike, and listing the day’s events.

Text of an anarchist poster distributed after the strike

The End of Obedience

You had to beat us, shoot us in the face, and gas us. You had to detain us and mistreat us, imprison us and isolate us. You had to threaten us with new laws and tell everyone we were “terrorists.” You had to do all that and more to try to get us to lower our heads. But despite everything you have done, you didn’t get what you wanted.

In the face of all your threats, all your orders and blackmails, on the 29th of March we lit bonfires in the streets. We weren’t a group, we weren’t 300 or even 2000. We were many more. We were those whom you trample every day, thinking we won’t defend ourselves. We were those you squeeze dry in precarious jobs. Those you turn out into the streets if you want to seize their houses or if they can’t pay the rent. Those you govern like resources, like numbers in your statistics. On the 29th of March, we disobeyed you and suddenly everything began to rumble. Now we are conscious of our strength. We feel your world crumbling and we won’t help you raise it up again.

We prefer to build our own. The end of obedience!

For Further Reference

Documentary: Barcelona March 29 General Strike

-

Most of the immigrants at that time were from southern Spain. ↩

-

Catalans opposed to Spanish occupation of their country. There are many different “indepe&drquo; organizations, most of them socialist, and many youth organizations. Leftwing Catalan political parties that participate in the Spanish government (e.g., the ERC) are considered indepes but often excluded by radical and socialist indepes. Catalanist fascists on the other hand are not considered indepes. ↩

-

The term invented by the press to lump together all social rebels deserving of repression and undeserving of a political voice. Because of the history in Catalunya, neither anarchists nor indepes could be explicitly targeted for repression without contradicting the sensitive democratic narrative, as both of these groups are widely known and thought to have political legitimacy. ↩

-

The CGT, the much larger of the two unions, is the result of a bitter split from the CNT that raged throughout the ‘80s, weakening the original organization. The CGT participates in the institutionalization of the labor unions achieved by the watershed Moncloa Pact (1977). Although the entire CNT rejected the pact, many CNT unions subsequently thought it necessary to accept the new reality and modify their principles, leading to a split. The splits eventually formed the CGT participate in workplace elections that assign official representatives to the workers, and accordingly they receive government subsidies. It should be noted that in the Spanish state, only legal labor unions can call a strike. If a general strike is official, all workers have the legal right to participate, although many employers do not respect this right. One downside of the tradition of labor struggles in Catalunya is that wildcat strikes are rarely considered, because combative labor unions exist, and the official strike is a longstanding social institution. ↩

-

The Cine Princesa riots followed the eviction of squatted social center, the Cine Princesa, on Via Laietana, on October 28, 1996. Participants in riots frequently disagree when ranking the importance and intensity of different uprisings. More than anything else, riots are subjective occurrences, and being in a different part of the city or having different standards will greatly change one’s evaluation. The riots of 29S spread spontaneously among thousands of people throughout several parts of the city, mostly as running engagements of short duration. The Cine Princesa riots involved focused and determined attacks by hundreds of people—squatters and some neighbors—against property and the police in one part of the center. ↩

-

At other times, the media readily used imagery of disorder and destruction to mobilize public support for repressing the antisistema; the difference in their strategy on May Day suggests a motive we can only infer. ↩

-

In Barcelona, the major avenues are constituted by a wide road flanked by strips of park and smaller side roads, so that large crowds will usually walk down the center road leaving buffers of emptiness on either side, useful for police movements or the maintenance of a peaceful atmosphere; the strips of park make it difficult, lacking strong will, to seize all three roads at once, as large crowds always walk down the center. ↩

-

In this case, not strictly sports hooligans, but marginalized and rowdy youth, as distinguished from people who consciously and habitually participate in social struggles, revolutionary projects, activist campaigns, or politics. ↩

-

The Catalan government, which forms an “autonomous community” within the Spanish state. ↩

-

The Spanish state was one of the first to elaborate a domestic politics of antiterrorism. The target, the independence struggle in Euskal Herria, the Basque country, was also a major public enemy of the Franco regime. Many of the victims of the antiterrorist laws were youths who participated in combative street protests against Spanish authority. Under the law, they could be arrested, tortured, and sentenced to long prison terms just the same as members of ETA. In other words, antiterror laws in Spain had already been adapted from focusing on armed guerrilla groups to focusing on horizontally organized street protests or autonomous sabotage. ↩

-

It is curious to note that both anarchists and rulers feel threatened by the expanded dissemination of riot porn through blogs, Facebook, and similar media. The anarchists fear the spectacularization of confrontation and publicizing of images that could help make arrests, whereas the State fears the autonomous, self-organized communication of imagery undermining media control. Note that in self-appointed First World countries, the media rarely spread images of large crowds attacking symbols of wealth or forces of order. ↩

-

While we should not predicate our struggle on an expectation that we are going to win, since we probably won’t, we should absolutely use the prospect of a future anarchy as an active imaginary that guides and colors our current practice. ↩

-

See Chris Ealham%squo;s Anarchism and the City; ignore his contradictory anti-insurrectionary strategic suggestions. ↩

-

CNT members, “cenetistas” in Spanish. ↩

-

An “ateneu,” or athenium, is a type of proletarian social center begun in the second half of the 19th century where workers and others could come together to educate themselves, hold study or debate groups, and other activities. “Llibertari” means libertarian, a common synonym for anarchist. ↩