This is the story of the occupation of a derelict building in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on November 12-13, 2011, told in the voices of a wide range of participants. While anarchists and corporate media have circulated news of this action far and wide, the experiences shared inside the building have remained a sort of black box. This report opens up that box, just as the occupiers opened up the building, to reveal a world of possibility.

Some of the narratives below are excerpted from longer accounts, which can be read in their entirety here.

Slideshow courtesy of Underground Reverie

In contrast to the occupation movement in some parts of the US, anarchists were involved in Occupy Chapel Hill from the very beginning, sending out the initial call and facilitating the first meetings. The points of unity consensed upon at the first gathering were based on the Pittsburgh Principles, and the group never adopted a nonviolence agreement.

At the second assembly, we debated whether to set up an encampment. Some argued against it, claiming that the police would evict us and insisting we should apply for a permit first. In nearby Raleigh, occupiers had applied for a permit but were only granted one lasting a few hours; everyone who remained after it expired was arrested. A few of us thought it better to go forward without permission than to embolden the authorities to believe we would comply with whatever was convenient for them.

A different facilitator would have let the debate remain abstract indefinitely, effectively quashing the possibility of an occupation, but ours cut right to the chase: “Raise your hand if you want to camp out here tonight.” A few hands went hesitantly up. “Looks like five… six, seven… OK, let’s split into two groups: those who want to occupy, and everyone else. We’ll reconvene in ten minutes.”

At first there were only a half dozen of us, but once we took that first step, others started drifting over. Ten minutes later there were twenty-four occupiers—more than we believed the local police were prepared to arrest—and that night fully three dozen people camped out in Peace and Justice Plaza. I stayed awake all night waiting for a raid, but it never came. We’d won the first round, expanding the zone of the possible.

On November 2, participants in the general strike in Oakland attempted to occupy an empty building that had previously provided services to the homeless. This controversial action ended in dramatic confrontations with riot police, but opened up a new horizon as winter crept up on the occupation movement.

Saturday, November 12, following the second annual Carrboro anarchist book fair, upwards of fifty people gathered for a march in solidarity with the occupation movement.

We couldn’t tell if we were parading yet. The crowd had begun to move, but it was still finding its rhythm and cohesion. But we two found our cue: there was a little boy, maybe five years old, carrying a black flag on the end of a six-foot bamboo pole. It tottered, sometimes bumping other paraders, as he struggled proudly and joyously to keep it aloft. We were with him.

Undercover officers were already following participants, peppering them with inappropriate questions.

This middle-aged white guy in a puffy red winter vest shuffled to catch up with us. Curious and clueless, he was in from “out of town,” he knew nothing about Anarchy or Occupy, and he was hoping we would explain things to him. Did we want to “smash capitalism?” Did we know what the plan was for tonight? Sometimes we couldn’t resist saying hilarious nonsense to him, but mostly we told him about how much we loved detective movies.

The march proceeded to the 10,000-square-foot commercial building at 419 West Franklin Street, a former Chrysler-Plymouth dealership empty since 2003. The absentee owner, Joe Riddle, was among the town’s most widely loathed property holders. He had no plans for the building; as it was sitting on property valued at close to a million dollars, only a powerful corporation could possibly purchase it.

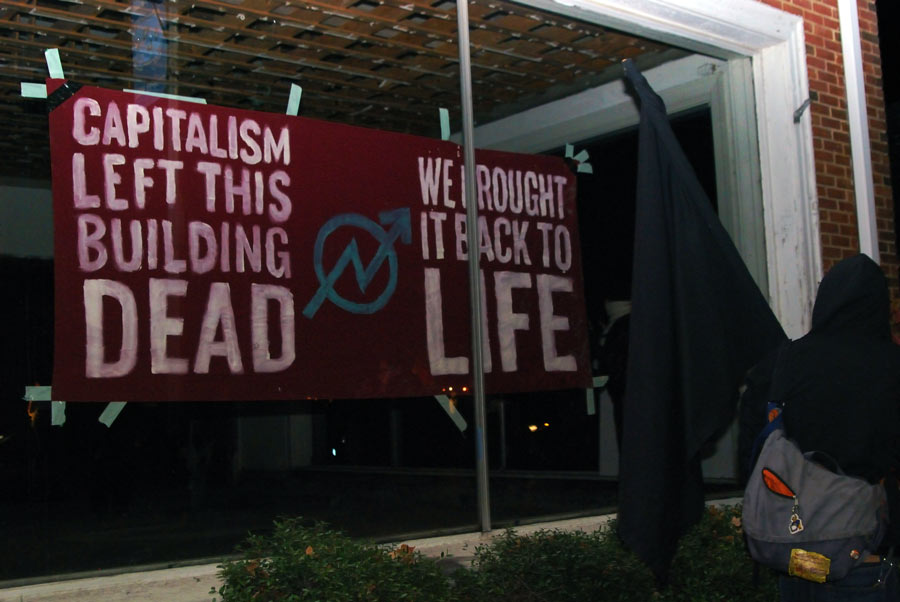

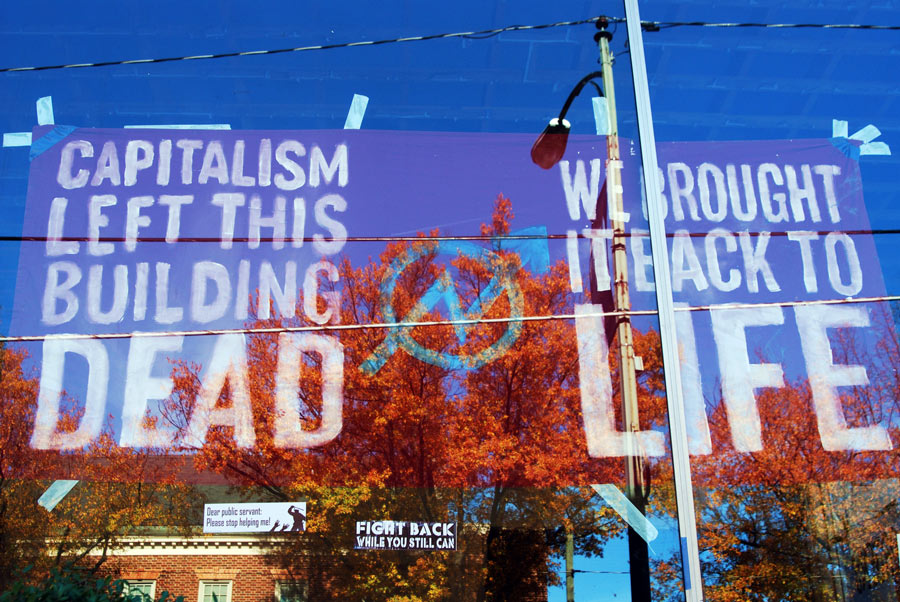

When we left the book fair, I had no idea what to expect, other than that we would be heading towards the plaza occupation. I was caught off guard by the large number of people and full of excitement as we made our way through a parking lot to the street. When we arrived, I was surprised to see the group move in the opposite direction. By the time we’d crossed the street to the building, I was so caught up in chanting and looking around at the crowd that I hadn’t taken stock of where I was. At this point, I looked toward the front of the march and saw that the windows of a building had been decorated with two large banners.

The march veered up the driveway in front of the building. As the crowd approached the vertical-sliding door, it glided up and two or three pairs of eyes stared out from under hats and over bandannas. As we streamed in, I saw people conversing and looking around the huge main room, silhouetted by the electric lights that had been rigged up and placed in the center. Someone handed me a folded sheet of paper that presented one of the most truly exciting ideas I had ever seen: the proposal that, amidst this global economic and political collapse, a community could form around this long-abandoned and maliciously wasted property and make something of benefit to the town at large. As I walked around the premises, I couldn’t believe that this was happening before my eyes. While I was caught entirely off-guard, I was eager to see where it would go.

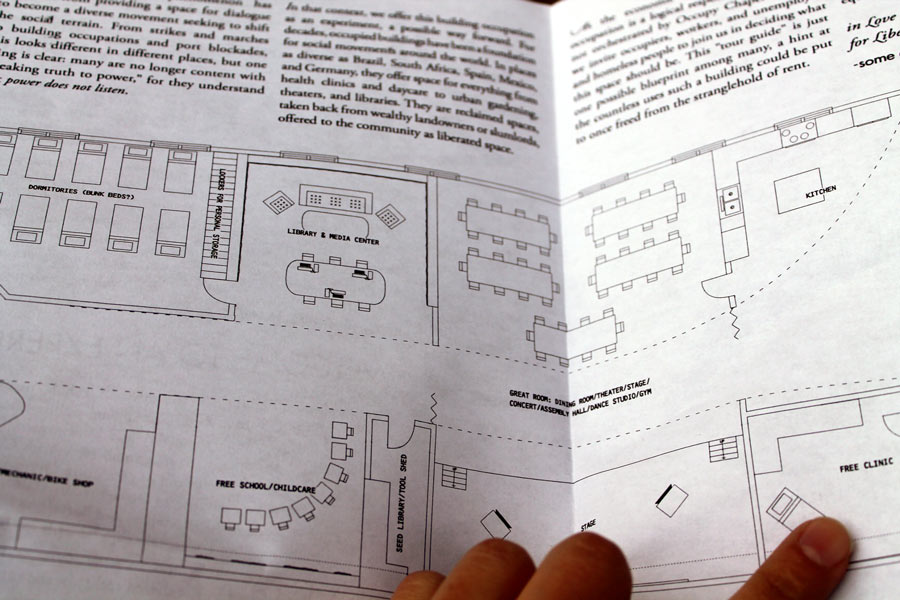

Participants distributed leaflets proposing that the space could be turned into a social center serving the community, including a meticulously designed blueprint showing some of “the countless uses such a building could be put to once freed from the stranglehold of rent.” Over the course of the evening, these handouts were warmly received by hundreds of passersby.

I stepped out to get some air. A couple approached me: “What’s going on here?”

I handed them the pamphlet and explained, “We’re turning this building into a community center.”

The man’s face lit up. “That’s great! I worked as a chef next door for years and this place just rots here!”

I nodded and added matter-of-factly, “It’s an illegal occupation.”

“Even better!” he said enthusiastically.

The leaflet spelled out an anticapitalist rationale for occupying the building, framing it in reference to the local context:

Across the US, tens of thousands of commercial and residential buildings sit empty while people sleep in the streets or descend into poverty paying ever-rising rent. Chapel Hill is no different. This building has been empty for a full decade, gathering dust and equity for a faraway landlord while rent skyrockets beyond our ability to pay. A brand new “green” development remains empty right up the street, gentrifying the neighborhood so longtime locals have to move to Durham. This is what happens when our town is shaped by profit rather than human need.

A handful of police officers positioned themselves across the street, a threatening but hesitant presence.

We had a police liaison ready and waiting, but they never initiated contact with us. When the police crossed the street towards the building, about fifty of us gathered in front of it, chanting “A—Anti—Anticapitalista!” The officers hesitated—what was this strange incantation?—and withdrew. That chant cast an enchantment, magically protecting the occupation.

Two people from the Chapel Hill Downtown Partnership also arrived; after the building had remained untouched for so many years, they had coincidentally just arranged for an artist to make a display in the front window. Occupiers engaged personably with them, exchanging contact information to open negotiations about the space. Later this was intentionally omitted from the authorities’ account of events, so as not to disrupt their narrative about dangerous and unapproachable anarchists.

Meanwhile, more and more people were arriving, passing through the open garage door to explore the building.

Vastness. Pure vastness. How can a building be so enormous? A single orange extension cord snaked across the vast concrete floor to a jury-rigged contraption of silver flood lamps. The warm grey yellow light flooded up and outwards to a massive ceiling of latticed wooden beams, casting crisscrossed shadows to the eaves of the roof beyond. The cinderblock walls seemed to extend out endlessly, an impossible distance, to a back door that had to be a football field away.

Some people began cleaning the interior; others set up a kitchen, a reading library, and sleeping areas. Trucks and cars were pulling up in the driveway one after another to unload supplies. A show originally scheduled in a local basement as an after-party for the book fair was moved to the occupation.

S— performed her set a cappella, kneeling on a blanket in that immense darkness with all of us pressed around her, a spark sailing up into the night. She’s always an amazing singer, but this was something else. When she opened her mouth, the whole world poured out: childbirth and tear gas, clear streams and mountaintop removal, rage and exaltation and tragedy.

Occupying a building means investing yourself in a space that may be taken from you any minute, in a time you know is short; it forces you to be present in a way we rarely are, to confront your own mortality. Death accompanies us at every step, devouring us instant after instant, but we only awaken to this when we stumble into unrepeatable moments. Without that awareness to give it urgency, music is only music; that night, it was existence itself, running through our fingers like sand.

R— joined her with his berimbau for the last song. When he hit the first note and paused, it echoed through the building and throughout our lives. Death and the police—the great erasers—were close at our heels, but for that moment we were immortal together, viscerally alive.

A joyous dance party ensued in the front room, as several dozen people cavorted with increasing abandon to live DJs while looped footage from the Oakland general strike was projected larger than life across the wall behind them. Over one hundred people from many different walks of life passed through the building in the course of the evening; locals who had only seen each other around town introduced themselves and conferred giddily. Many of these were younger anarchists, students, and hipsters employed in the service industry, but others were long-established residents old enough to recount stories from the days before the automobile dealership closed. There were even a few attendees who possessed positions of influence at the university or in local politics; later, of course, it never came up that they had participated exuberantly in an illegal occupation.

The most exciting thing for me about occupying this building was the looks on my friends’ faces. Surprise. Accomplishment. Possibility. Unbridled joy.

None of us thought we could hold this building, but several hours in we were still dancing, still chatting with passersby, still dreaming about what would come next. What if this building could actually be ours? What if we could be powerful enough together to build the beautiful things we deserve? I had so many conversations with strangers about what we can make and be for each other outside the constraints of capitalism, so many daydreams about living in a world where everyone has enough—and on each of these new friends’ faces, I found the resolve to make something worth taking risks for.

As the festivities finally died down, about two dozen people settled in to sleep in the building overnight, securing the doors and unrolling sleeping bags on cardboard and wooden pallets. Others stood watch—some inside, some outside—waiting to sound the alarm in case of a police raid.

Occupy Chapel Hill had encamped in the only public space in Chapel Hill, a concrete plaza outside the building that serves as post office and courthouse, located at the edge of a long stretch of bars. At 2 a.m. every night, patrons stumble from the bars, tearing down signs, kicking tents, and shouting obscenities at occupiers. No wonder so many occupiers fled to Occupy Chrysler for the cavernous safety of the abandoned car dealership at the other end of the street. While four or five members of OCH waged the stressful nightly battle to deescalate intoxicant-fueled anger at the plaza, I settled with one companion on the stoop in front of the Chrysler building to stay awake and watch while weary occupiers got some well-deserved rest.

Traffic dwindled, leaving only a cold quiet street of brick buildings and gold-leafed trees, a few stars, and the just-waning moon. In those quiet hours before dawn, anything seemed possible in the town where we both had lived most of our lives. If the landlord antagonistic to the town let us stay, if the town antagonistic to the landlord let us stay, if a nonprofit arts organization with tentative access to the building partnered with us, if any of those things happened we had the skills among us to winter off the grid easily. At three times the size of the public plaza, the hulking building behind us not only offered room for Occupy’s general assemblies, teach-ins, and sleeping, but ample space to become whatever a community envisioned: a kitchen, a clinic, a classroom, a library, a movement and arts space. It seemed all we had to do was wait for morning and begin.

Police officers dropped by in the morning, unsuccessfully seeking to gather intelligence from those on watch duty. This visit was also omitted from their later narrative of events. The artist who had been invited by the Downtown Partnership to decorate the storefront showed up shortly thereafter; a friend of participants in Occupy Chapel Hill, she expressed support for the occupiers. This didn’t prevent enemies of the occupation from later using her as an excuse to justify the raid.

An assembly discussing anarchist strategies against the prison-industrial complex had been planned for the book fair venue at noon. It was moved to the front room of the occupation; dozens of people participated, sticking around afterwards for lunch catered by a supportive local restaurant. Others, several of whom were carpenters or construction workers by trade, were busy fixing up the building: sweeping the floors, unboarding the windows, and building structures to supplement the furniture dropped off by enthusiastic locals.

After lunch, a rumor circulated that the police were preparing to raid the space. A few dozen of us gathered for an impromptu meeting. It struck me how different this was from the general assemblies of Occupy Chapel Hill. Those were often bureaucratic nightmares, breeding boredom and aggravation as people deadlocked over minutia and droned on just to hear themselves speak.

Here, there was nothing abstract about the issues at hand, nothing that promoted pointless arguing or ego trips. We were putting our bodies on the line just by being present; these were real choices that would have immediate consequences for all of us. For once, we didn’t need a facilitator to listen to each other or stay on topic. With our freedom at stake, we had every reason to work well together. Maybe the problem at the plaza had been that we weren’t risking enough.

We decided that if the police came and it was clear we couldn’t keep the building, we would all leave in a group, taking our belongings with us and being sure not to leave anyone in their hands. They must have had that meeting infiltrated or else they wouldn’t have known to swoop in right after it; later, they claimed they were afraid we were dangerous, but their real fear must have been that we would bring the occupation to a close on our own terms, without any losses.

Many people hurried home from this meeting to get more supplies and return to the building prepared to hold it for the long haul. The police took this opportunity to carry out a fully militarized raid.

I was sitting on the brick edge of the flowerbed, drinking coffee and sharing a chocolate bar with friends, alternately watching Franklin Street’s pedestrians and glancing at the yoga class beginning inside our building. The conversation was lighthearted; we were all dizzy with the excitement of taking a stand against the wastefulness of the property owner. We feared our joy might be short-lived—we anticipated being quickly evicted, and had committed to a plan to leave peacefully when the police arrived—but nevertheless, we were reveling in our future plans for the community center we hoped to establish.

I was suddenly distracted by the headlights of a white SUV, growing larger and larger in the back door of the building. I heard someone inside yell “POLICE!” I pictured a few officers arriving to tell those inside the building that it was private property, that they had to vacate or be arrested. I sighed and began to collect my belongings.

But as I rounded the corner of the building, I was met by a group of police officers and Special Emergency Response Team members—my brain automatically labeled them “soldiers.” Some were wearing familiar black Chapel Hill Police Department uniforms; others green fatigues and tactical vests. All were carrying loaded weapons—automatic rifles and handguns. Many had belts loaded with extra cartridges, ammunition, and plastic zip-tie handcuffs. They were running towards me, pointing their guns and screaming “ON THE GROUND! EVERYBODY ON THE GROUND! FACES ON THE PAVEMENT!”

I paused. Surely they don’t mean me, I thought. Surely they aren’t carrying those guns because they’re scared of me. Knowing that I was outside, and that my bag only contained notebooks, pamphlets, and a coffee thermos, it seemed impossible that these police officers were really running towards, really screaming at, really aiming their weapons at me. I took a moment to set my half-empty cup of coffee on the edge of the flowerbed. But as the barrels of their rifles drew closer, I realized yes, they are running at me. I threw myself to the concrete, face down.

I listened to my own ragged, heavy breathing and the sounds of boots. I was torn between the visceral need to see the friends I had been sitting with and a fear that made me squeeze my eyes tightly shut. I focused on my breathing—in, out, in, out. What would have happened if I’d hesitated any longer before falling to the pavement? Would they have fired? If I’d reached into my pocket to protect my phone, would they have killed me?

I heard a man’s gruff voice above me: “Please place your hands at the small of your back.” A second passed before I realized he was addressing me. I took my hands from beneath my face and placed them behind me. I felt him take my hands and pull one through each loop of the plastic handcuffs. I heard the tk-tk-tk-tk ratcheting of the cuffs being tightened. I remained face down on the sidewalk. I counted seventy-two of my own deep breaths.

An operation coordinated between multiple police departments shut down several blocks of Franklin Street, Chapel Hill’s primary artery, for over an hour while officers waving assault rifles stormed the building. They arrested eight people and detained many more, including journalists and legal observers. Ironically, the city bus requisitioned by police to hold arrestees bore an advertisement for Wells Fargo on the side. A large crowd immediately gathered across the street chanting “Shame!” and “Police, Police, the Army of the Rich!” and explaining the circumstances of the raid to curious passersby.

That evening, less than six hours later, a spirited solidarity march of nearly a hundred people took the streets of downtown Chapel Hill, marching around the main thoroughfares chanting “Occupy Everything” and “We’ll Be Back.” Some carried black flags; others bore banners reading “Under Capitalism We’re All Under Gunpoint” and “Fight Back.” The majority of the participants marched as a black bloc, sending a clear message that they were not intimidated; many supporters and curious passers-by followed behind.

I’m not the kind of person who gets up in front of people to tell them what I think—I’m usually too nervous to address even a small crowd. But that night I felt like my voice was the voice of all the women in the march; my voice was as strong as one hundred people’s voices, screaming, “Cops, Pigs, Murderers!” at the top of my lungs. Afterwards, I told my friend that I felt like I needed to yell for all the ladies, because I wanted to be sure everyone would hear us, too. I yelled as loudly as I could. It was hard to imagine a reason to be anywhere but there, surrounded by the most awesome human beings I know, in that beautiful moment.

The march was followed by a benefit show packed with well over a hundred people. Locals and visitors from around the state expressed solidarity with the arrestees, the building occupation, and the anticapitalist movement. The owners of the venue had openly approved of the black bloc assembling there and returning after the march; this marked a watershed gain in public support for anarchists in Chapel Hill.

Everyone was there, even the Women’s Studies professor I’d dated—my housemate loaned her his scarf for the black bloc. Our band somehow ended up playing, too, even though we weren’t on the bill and hadn’t practiced in half a year; people were waving black flags in the air as they danced. The whole weekend was like an anarchist cartoon, with all the clichés crowded in back to back: the book fair, the workshop, the squat, the assembly, the raid, the march, the show. I hadn’t slept in something like 72 hours; things were starting to feel surreal. Had those blonde students with black sweatshirts over their UNC gear been real? Were they really shouting “Fuck the Police!” with us?

Monday afternoon, dozens of protesters disrupted the press conference at which the mayor and police chief attempted justify the raid. This swift response prevented the authorities from spinning a narrative of public support and likely contributed to later public willingness to express disapproval. Media attention continued to focus on outrage against the police rather than the violation of property rights.

That evening, Occupy Chapel Hill gathered for a contentious general assembly at the original encampment. There were more people in attendance, and more energy, than there had been at any general assembly since its inception; whether or not one approved of the building occupation, it had undeniably breathed life into the local movement as well as garnering it national attention. The discussion revealed that the differences within Occupy Chapel Hill were hardly fatal. In subsequent general assemblies it became clear that the building occupation had radicalized many if not most participants, further expanding their notion of the possible.

Over the following week, people inspired by the efforts in Oakland and Chapel Hill occupied buildings in Saint Louis, Washington, DC, and Seattle. This new wave of actions pushed the Occupy movement from symbolic protests towards directly challenging the sanctity of property.

photo by Nancy Munoz

On Thursday, over one hundred people marched up Franklin Street expressing solidarity with occupiers worldwide and reaffirming their opposition to the raid; many of them were taking the street for the first time. The following Monday, two hundred people from a wide range of demographics assembled at the police station, marched without a permit down a major boulevard to the town hall, and continued to block traffic and raise a ruckus for hours while some of them entered the city council meeting to speak out or disrupt it. Local government was in disarray, the police were powerless to do anything with public disapproval at an all-time high, and a diverse social movement was coming together around anarchist-initiated efforts. A solidarity march the same night in Atlanta underscored how widely the ripples from the building occupation had spread.

This story demonstrates how swiftly a social movement can take off when a few individuals seize the right opportunity to push the envelope. By creating an open, irresistible space that transformed all who passed through it, the occupiers shifted the political landscape in a single night. The authorities were confronted with a no-win situation: they had to choose between ceding territory and discrediting themselves in the public eye. Swift follow-up enabled anarchists to turn subsequent attempts at repression into additional opportunities to forge connections and spread the virus of resistance.

As the economy worsens and social conflict intensifies, the conditions will be increasingly ripe for contesting the physical territory of capitalism. But this can only succeed and spread when it is viewed above all as a way to fight for social territory. The relationships we build in the process of fighting are the territory we win, even more than the plazas and buildings we seize.

I do not feel that we lost, even when I walk down Franklin Street and read the “condemned” sign now posted out front. The sense of possibility remains; there is a new intensity when we mask up for a black bloc downtown, an aliveness that pulls on those around us. My only regret is that we never got to name our space. Its memory persists, but incommunicable, faceless. If I fight now, it is not only to honor that memory, but also to give it form for all those who can only imagine it in the abstract. We will be back. Next time we’ll be ready.

Appendix